Battle of Spotsylvania • Tour the Battlefield • Monuments & Markers • The Armies

The Spotsylvania Battlefield Exhibit Shelter is at Stop 1 on the Spotsylvania Battlefield Auto Tour. The three walls of displays in the shelter provide an excellent summary of the battle and are the perfect starting point for a visit to the Spotsylvania Court House battlefield.

The Spotsylvania Battlefield Exhibit Shelter is at Stop 1 on the Spotsylvania Battlefield Auto Tour. The three walls of displays in the shelter provide an excellent summary of the battle and are the perfect starting point for a visit to the Spotsylvania Court House battlefield.

The fifteen displays are listed in order from left to right around the building.

South Wall Displays – A Different Kind of War

A Different Kind of War exhibit

Text from the exhibit:

A Different Kind of War

With the 1864 Overland Campaign, the war in Virginia changed. The old pattern of fight, retreat, and rest yielded to Ulysses S. Grant’s relentless maneuvering and fighting. Attacked in superior force by an incessant foe, Southern troops protected themselves behind stout earth-and-log defenses. Union efforts to drive them from those works led to some of the most desperate combat in American history.

The Race to Spotsylvania exhibit

Text from the exhibit:

The Race to Spotsylvania

The Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River on May 4, 1864, and engaged Lee’s army in the region known as the Wilderness. When two days of fighting failed to produce victory, Grant ordered a night march to Spotsylvania Court House. “My object in moving to Spotsylvania…,”he wrote, was “to get between [Lee’s] army and Richmond if possible, and, if not to draw him into the open field.”

Lee, however, anticipated Grant’s move. Starting late on May 7, General Richard H. Anderson rushed his corps to Spotsylvania by a parallel route, arriving just minutes ahead of the Union column. The armies clashed on a low ridge known as Laurel Hill (about 600 yards southwest of you). Stalemate gave time for the rest of Lee’s army to arrive. That night, both sides started digging. Two weeks of trench warfare followed.

Caption to the background image:

The Union army’s objective was Spotsylvania Court House, a village of just a few hundred inhabitants. Whoever controlled Spotsylvania would hold the inside track in Richmond.

Caption to the map inset:

After sunset, May 7, General Gouverneur K. Warren’s Fifth Corps left its trenches in the Wilderness and started for Spotsylvania Court House by way of the Brock Road. Anderson’s Confederates meanwhile, marched to Spotsylvania by a route farther to the west.

Caption below the photo:

General Richard H. Anderson’s decisive action on May 8 saved Spotsylvania Court House for the Confederacy.

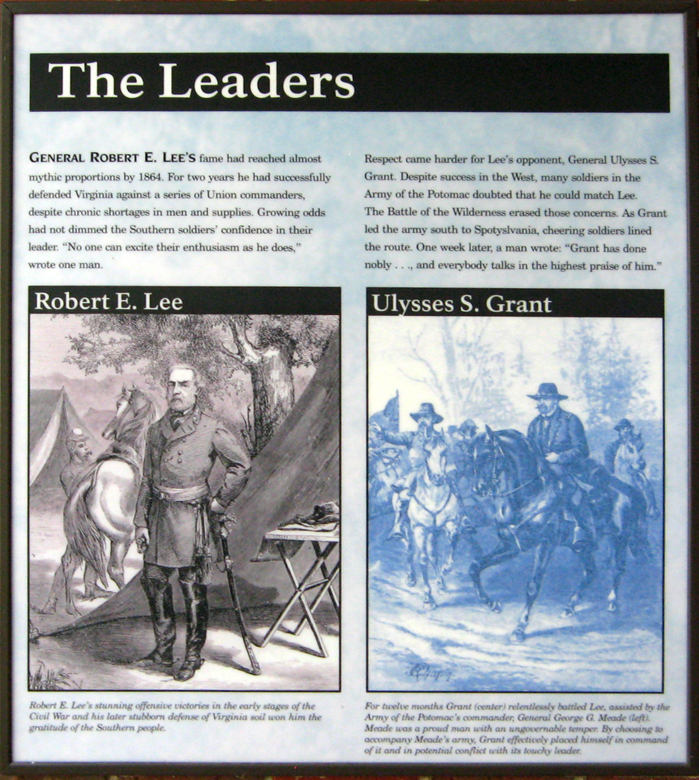

The Leaders exhibit

Text from the exhibit:

The Leaders

General Robert E. Lee’s fame had reached almost mythic properties by 1864. For two years he had successfully defended Virginia against a series of Union commanders, despite chronic shortages of men and supplies. Growing odds had not dimmed the Southern soldiers’ confidence in their leader. “No one can excite their enthusiasm as he does,” wrote one man.

Respect came harder for Lee’s opponent, General Ulysses S. Grant. Despite success in the West, many soldiers in the Army of the Potomac doubted that he could match Lee. The Battle of the Wilderness erased those concerns. As Grant led the army south to Spotsylvania, cheering soldiers lined the route. One week later, a man wrote: “Grant has done nobly…, and everybody talks in the highest praise of him.”

Caption to Robert E. Lee:

Robert E. Lee’s stunning offensive victories in the early stages of the Civil War and his later stubborn defense of Virginia soil won him the gratitude of the Southern people.

Caption to Ulysses S. Grant:

For twelve months Grant (center) relentlessly battled Lee, assisted by the Army of the Potomac’s commander, General George G. Meade (left). Meade was a proud man with an ungovernable temper. By choosing to accompany Meade’s army, Grant effectively placed himself in command of it and in potential conflict with its touchy leader.

A War of Attrition exhibit

Text from the display:

A War of Attrition

At Spotsylvania Court House, the art and horror of trench warfare reached new levels. Faced with Grant’s superior numbers, the Confederates constructed a line of earthworks six miles long – from the Po River on the left to a point beyond Spotsylvania Court House on the right. The Federals dug in too, their line paralleling the Confederates’, about 400 yards away.

“I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer.”

General Ulysses S. Grant, USA

By the time the armies left Spotsylvania, they had been fighting, digging, and maneuvering for more than two weeks – sometimes in stifling heat, at other times in knee-high mud. They were hungry, dirty, and above all exhausted. Many men fell out of the ranks from fatigue; others plodded on, nearly senseless from lack of sleep.

Tired of killing, tired of marching, tired of simply being tired, soldiers on both sides could only wonder, “…will this wail of woe that rises from the bloody battlefields never cease?”

Caption to the background painting:

“The Last Recall” by Julian Scott, courtesy of the

Drake House Museum/Plainfield Historical Society.

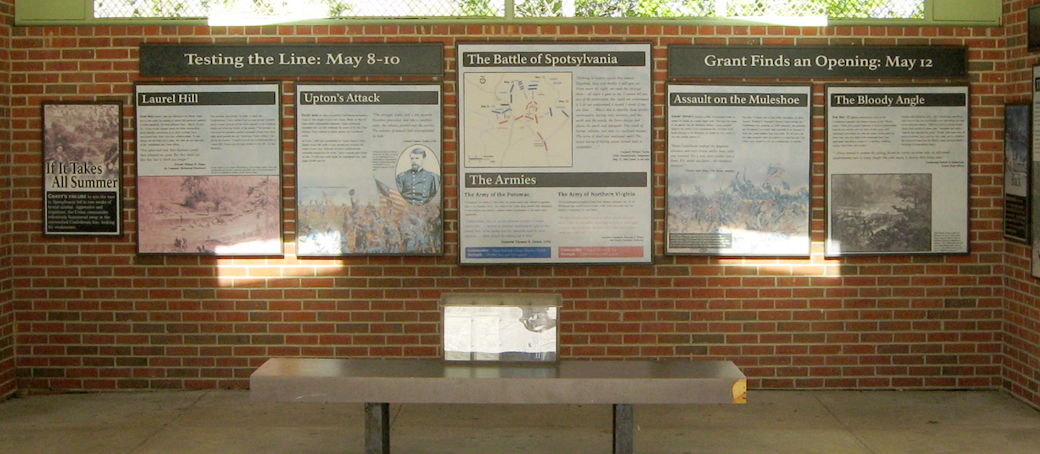

West Wall Displays – If it Takes All Summer

Text from the display:

If It Takes All Summer

Grant’s failure to win the race to Spotsylvania led to two weeks of brutal combat. Aggressive and impatient, the Union commander relentlessly hammered away at the entrenched Confederate line, looking for weakness.

Testing the Line: May 8-10

Text from the display:

Laurel Hill

Less well known than the fighting at the Bloody Angle but no less costly, the combat at Laurel Hill produced upwards of 5,000 casualties. On three different days – May 8, 10, and 12 – Union troops charged across the fields surrounding Sarah Spindle’s farmhouse in an effort to break Lee’s entrenched lines. Each time they suffered defeat. “It was charge and fall back 6 to 8 times. We could get our men only so far,” complained one officer.

“One good rush and their bayonets would have silenced our guns. But they could not face that hail of death any longer.”

Private William M. Dame,

1st Company, Richmond Howitzers

The problem was terrain. In order to reach the Confederates, Union soldiers had to cross several hundred yards of open ground, all the while exposed to the bursting shells and whizzing bullets of the enemy. “The moment we rose from the ground a perfect hailstorm of ball from three sides were poured into us,” wrote one Union soldier, “men fell by the dozens.” Unable to crack the Confederate line at Laurel Hill, Grant cast his gaze further to the left – to the Muleshoe.

Caption to the drawing:

In this sketch of the Laurel Hill fighting, Union troops (center) leave their earthworks and charge across the open field, only to be pinned down by the fire of Confederate soldiers on the distant ridge.

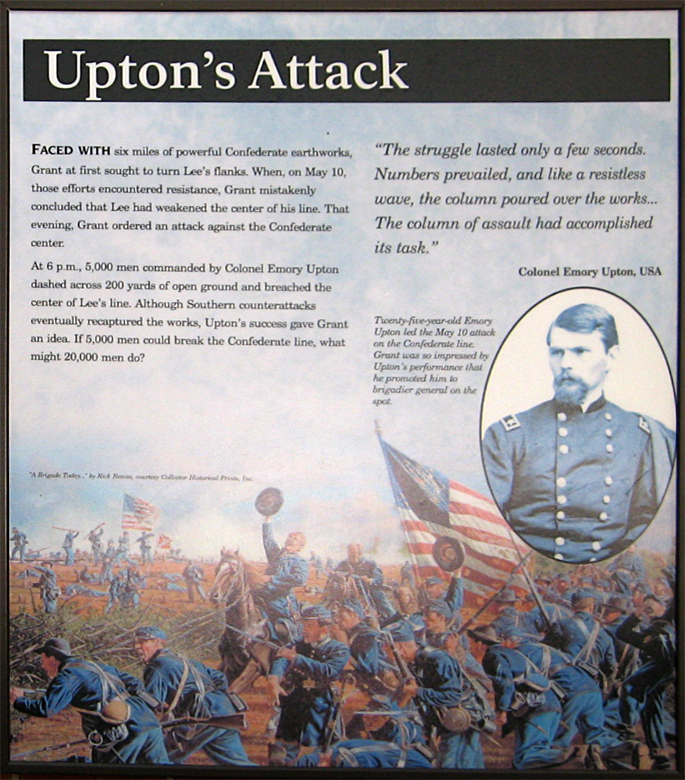

Text from the display:

Upton’s Attack

Faced with six miles of powerful Confederate earthworks, Grant at first sought to turn Lee’s flanks. When, on May 10, those efforts encountered resistance, Grant mistakenly concluded that Lee had weakened the center of his line. That evening, Grant ordered an attack against the Confederate center.

At 6 p.m., 5,000 men commanded by Colonel Emory Upton dashed across 200 yards of open ground and breached the center of Lee’s line. Although Southern counterattacks eventually recaptured the works, Upton’s success gave Grant an idea. If 5,000 men could break the Confederate line, what might 20,000 men do?

“The struggle lasted only a few seconds. Numbers prevailed, and like a resistless wave, the column poured over the works…The column of assault had accomplished its task.”

Colonel Emory Upton, USA

Caption to the inset photo:

Twenty-five-year-old Emory Upton led the May 10 attack on the Confederate line. Grant was so impressed by Upton’s performance that he promoted him to brigadier general on the spot.

Caption to the background painitng:

“A Brigade Today…” by Rick Reeves, courtesy Collector Historical Prints, Inc.

Text from the display:

The Battle of Spotsylvania

“Nothing in history equals this contest. Desperate, long and deadly, it still goes on. From morn till night, nor ends the carnage there — all night it goes on too. I cannot tell you any of the particulars. You could not understand it. I do not understand it myself. I doubt if any one does… Who’s able to describe these terrific cannonades, tearing men, animals, and the earth and the woods, the fierce charge and shout, the panic and stampede. The crush of horses, vehicles, and men [in] confused masses. The acres of dead and mutilated men? The usual course of feeling seems turned back or suspended…”

Corporal William Taylor

110th Pennsylvania Volunteers

May 17, 1864, letter to his wife

The Armies

The Army of the Potomac

Throughout the winter of 1863-1864, the armies rested and refitted on opposites sides of the Rapidan River. The ranks of the Union army swelled with thousands of new draftees and recruits – soldiers whose commitment to the cause many questioned.

“I determined, first, to use the greatest number of troops practicable…; second, to hammer continuously against the armed force of the enemy and his resources until by mere attrition…there would be nothing left to him.”

General Ulysses S. Grant, USA

Commander: Major General George Gordon Meade

Strength: 100,000 men and 344 cannon

The Army of Northern Virginia

The Confederates struggled to keep their existing regiments full. In the Wilderness they would bring to the battle 13,000 fewer men than they had fielded at Gettysburg the year before.

“We had all discussed Grant in camp, and it was well known that he had taken command to hold on and fight until we were worn out. He could lose men and replace them, we could not.”

Assistant Surgen Thomas F. Wood,

3rd North Carolina Infantry

Commander: General Robert E. Lee

Strength: 55,000 men and 228 cannon

Grant Finds an Opening: May 12

Text from the display:

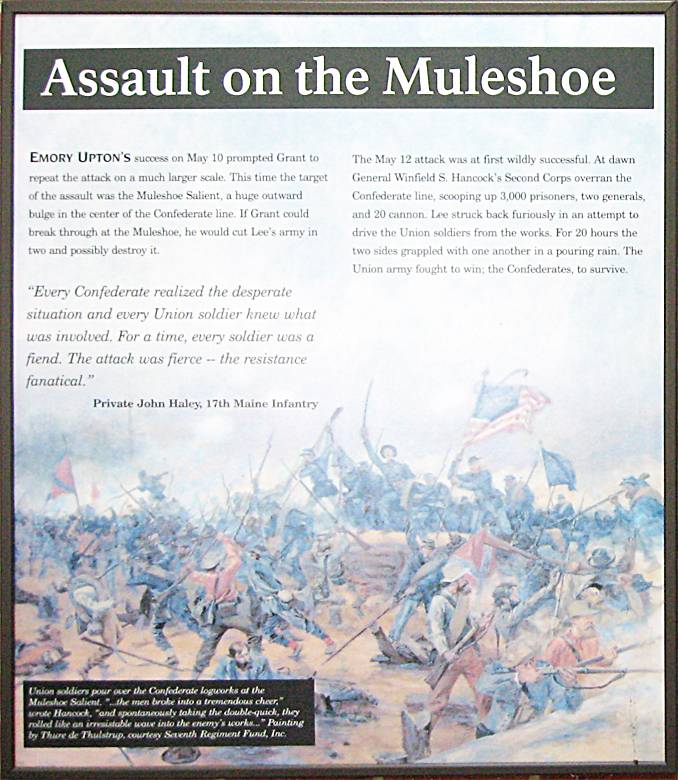

Assault on the Muleshoe

Emory Upton’s success on May 10 prompted Grant to repeat the attack on a much larger scale. This time the target of the assault was the Muleshoe Salient, a huge outward bulge in the center of the Confederate line. If Grant could break through at the Muleshoe, he would cut Lee’s army in two and possibly destroy it.

“Every Confederate realized the desperate situation and every Union soldier knew what was involved. For a time, every soldier was a fiend. The attack was fierce — the resistance fanatical.”

Private John Haley, 17th Maine Infantry

The May 12 attack was at first widely successful. At dawn General Winfield S. Hancock’s Second Corps overran the Confederate line, scooping up 3,000 prisoners, two generals, and 20 cannon. Lee struck back furiously in an attempt to drive the Union soldiers from the works. For 20 hours the two sides grappled with one another in a pouring rain. The Union army fought to win; the Confederates, to survive.

Caption to the background painting:

Union soldiers pour over the Confederate logworks at the Muleshoe Salient. “…the men broke into a tremendous cheer,” wrote Hancock, “and spontaneously taking the double-quick, they rolled like an irresistible wave into the enemy’s works…” Painting by Thure de Thulstrup, courtesy Seventh Regimental Fund, Inc.

Text from the exhibit:

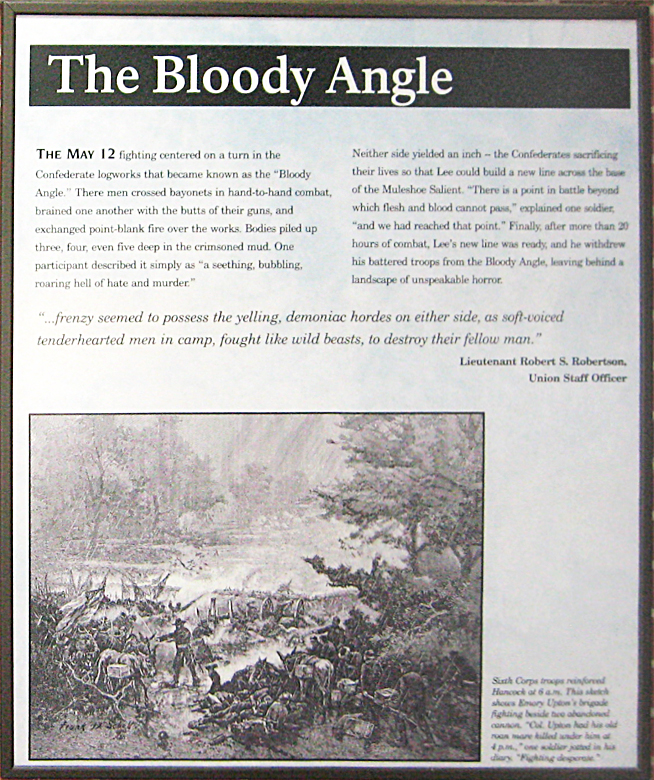

The Bloody Angle

The May 12 fighting centered on a turn in the Confederate logworks that became known as the “Bloody Angle.” There men crossed bayonets in hand-to-hand combat, brained one another with the butts of their guns, and exchanged point-blank fire over the works. Bodies piled up three, four, even five deep in the crimsoned mud. One participant described it simply as “a seething, bubbling, roaring hell of hate and murder.”

Neither side yielded an inch — the Confederates sacrificing their lives so that Lee could build a new line across the base of the Muleshoe Salient. “There is a point in battle beyond which flesh and blood cannot pass,” explained one soldier, “and we had reached that point.” Finally, after more than 20 hours of combat, Lee’s new line was ready, and he withdrew his battered troops from the Bloody Angle, leaving behind a landscape of unspeakable horror.

“…frenzy seemed to posses the yelling, demonic hordes on either side, as soft-voiced tenderhearted men in camp, fought like wild beasts, to destroy their fellow man.”

Lieutenant Robert S. Robertson

Union Staff Officer

Caption to the drawing:

Sixth Corps troops reinforced Hancock at 6 a.m. This sketch shows Emory Upton’s brigade fighting beside two abandoned cannon. “Col. Upton had his old roan mare killed under him at 4 p.m.,” one soldier jotted in his diary, “Fighting desperate.”

North Wall displays – No Turning Back

Text from the exhibit:

No Turning Back

Defeated but undeterred, Grant abandoned Spotsylvania’s blood-soaked fields on May 21 and continued south — toward Richmond and ultimate victory. In his wake he left a scarred landscape pitted with thousands of graves.

Text from the display:

The Awful Arithmetic

If considered as one engagement, the fighting at Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House constitutes the bloodiest single battle in American history. Some 36,000 Union soldiers and 24,000 Confederates were killed, wounded, captured, or missing during the period of May 5 to May 21, 1864 — a staggering 30 percent of those engaged.

The tremendous loss of life outraged many in the North, some of whom labeled Grant a butcher. But the general understood his arithmetic. He could replace his losses, Lee could not. In time he would grind the Confederate army down to a point where it could no longer resist. Grant had engaged Lee in a war of attrition — a war the South could not win.

“…In the long run, we ought to succeed, because it is in our power more promptly to fill the gaps in men and material which this constant fighting produces.”

General George G. Meade, USA

Caption to the background photo:

Confederate Soldiers, killed in the May 19 fighting near the Alsop House, lie in rows awaiting burial.

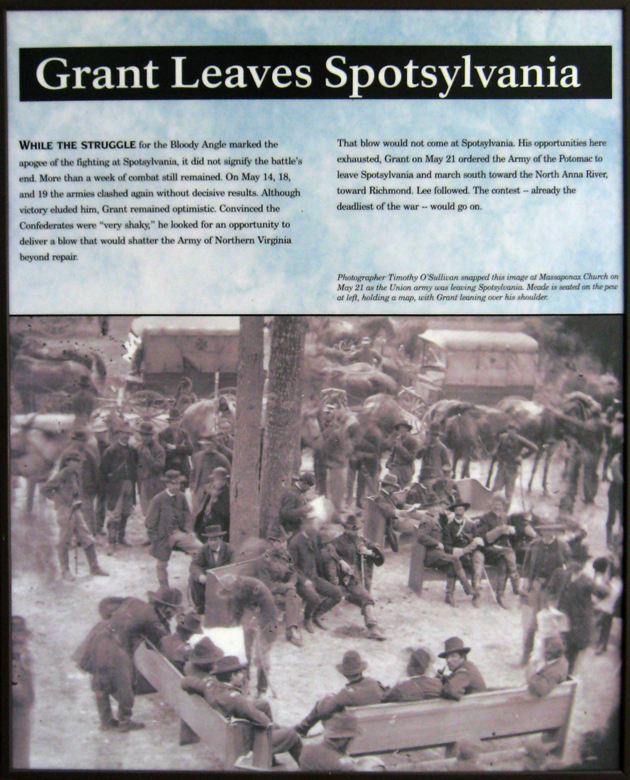

Text from the display:

Grant Leaves Spotsylvania

While the struggle for the Bloody Angle marked the apogee of fighting at Spotsylvania, it did not signify the battle’s end. More than a week of combat still remained. On May 14, 18, and 19 the armies clashed again without decisive results. Although victory eluded him, Grant remained optimistic. Convinced the Confederates were “very shaky,” he looked for an opportunity to deliver a blow that would shatter the Army of Northern Virginia beyond repair.

That blow would not come at Spotsylvania. His opportunities here exhausted, Grant on May 21 ordered the Army of the Potomac to leave Spotsylvania and march south toward the North Anna River, toward Richmond. Lee followed. The contest — already the deadliest of the war – would go on.

Caption to the photo:

Photographer Timothy O’Sullivan snaped this image of Massaponax Church on May 21 as the Union army was leaving Spotsylvania. Meade is seated on the pew at left, holding a map, with Grant leaning over his shoulder.

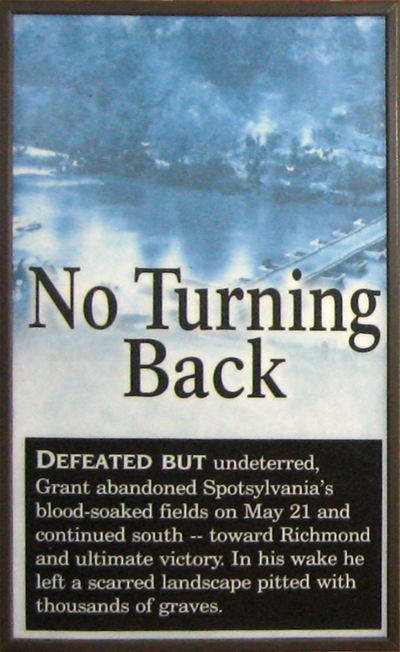

Text from the exhibit:

A Hard Road to Travel

Wilderness and Spotsylvania were opening battles in a yearlong campaign that only ended with Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House. Before reaching Appomattox the armies would clash again at North Anna River, Cold Harbor, Petersburg, and places in between. Thousands more would die before the fighting ceased.

“The great battle is not yet over, there is only a lull — the first for twenty-five days, the sullen roar of artillery even now reminds us that the last act of the bloody tragedy is yet to be enacted.”

Captain Andrew J. McBride,

10th Georgia Infantry

Caption to the photo:

The armies’ next collision was twenty-five miles south of Fredericksburg, on the banks of the North Anna River. Unwilling to attack Lee there, Grant again shifted south and headed for Cold Harbor.

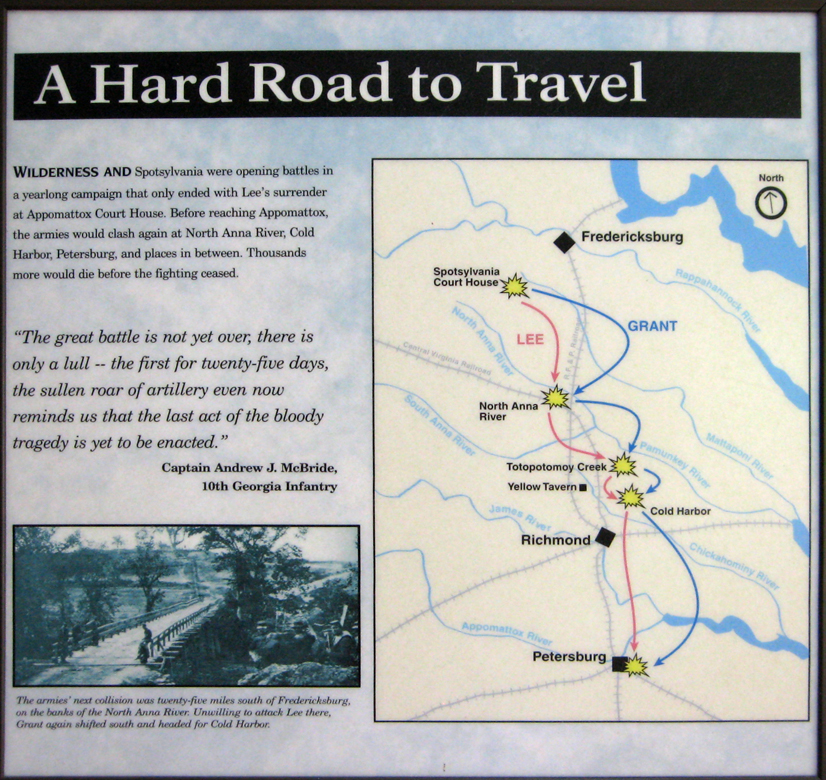

Text from the display:

Those Left Behind

Casualties at Spotsylvania were appalling. “The question became, pretty plainly, whether one was willing to meet death, not merely run the chances of it,” wrote one Confederate soldier. These are the faces of just a few of the 4,000 Union and Confederate soldiers who died in the battle. The graves pictured at the bottom of this panel belonged to Mississippi soldiers killed at the Bloody Angle.

Map and directions to Tour Stop 1 – Spotsylvania Battlefield Exhibit Shelter

Tour Stop 1 is on the west side of Grant Drive 150 yards north Brock Road, Virginia Route 613. (38°13’08.7″N 77°36’50.2″W)

Tour Stop 1 is on the west side of Grant Drive 150 yards north Brock Road, Virginia Route 613. (38°13’08.7″N 77°36’50.2″W)

(return to the main Stop 1 page)

(return to the main Battle of Spotsylvania Auto Tour page)