Campaign Overview * Campaign Timeline

Shenandoah 1862 Campaign Timeline

|

March

|

|

| March 9 |

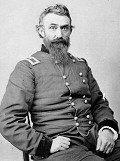

Confederate Major General Thomas J. Jackson Union Major General Nathaniel Banks crossed the Potomac with two divisions of infantry and a strong cavalry command. Confederate Major General Thomas J. Jackson, commanding the Valley District, evacuated Winchester and moved 42 miles south up the Shenandoah Valley to Mount Jackson. (The Shenandoah Valley rises in elevation from north at the Potomac River to south, so going “up” the Valley meant rising in elevation, or going south.) |

| March 12 | Banks moved into Winchester, the first of many times the town would change hands during the Civil War. |

| March 21 | Jackson’s cavalry commander, Turner Ashby, reported to Jackson that two divisions of Banks’ force were leaving the Valley and returning to the Washington area. |

| March 22 | Jackson force marched his men 25 miles north. Ashby’s cavalry skirmished with Federals, and Federal commander Shields was wounded by a shell fragment. He sent two of his brigades south of Winchester and the third out of town to the north, but had it halt outside of town in reserve. He then turned over field command to Colonel Nathan Kimball. Southern loyalists in Winchester reported to Jackson that only four Union regiments were left at Winchester when in reality there was a division of over 9,000 men. |

| March 23 |

Battle of Kernstown Union Colonel Nathan Kimball |

| March 24 | Kimball launched a pursuit of Jackson at first light, causing Ashby’s cavalry to panic. But Banks called off hot pursuit due to supply problems. |

| March 27 | Jackson retreated to Mount Jackson, slowly followed by Banks. Jackson ordered Captain Jedediah Hotchkiss to “make me a map of the Valley, from Harpers Ferry to Lexington, showing all the points of offense and defense.” |

| April | |

| April 1 | Banks moved forward to Woodstock, about 12 miles north of Mount Jackson, where supply problems again stopped him. Jackson fell back about five miles to Rude’s Hill. |

| April 4 | The Federal Department of the Shenandoah was re-created, consisting of the Valley of Virginia, the Counties of Washington and Allegheny in Maryland and such parts of Virginia “as may be covered by the army in its operations.” The Fifth Corps was discontinued and moved into the Department of the Shenandoah with its organization unchanged. |

| April 16 | Banks moved forward again surprising Ashby and capturing 60 of his men by crossing Stony Creek at an unguarded ford. |

| April 18 | Jackson fell back from Rude’s Hill to Harrisonburg. |

| April 19 | Jackson marched 20 miles to the east via Swift Run Gap, leaving the Shenandoah Valley. Banks moved forward and occupied New Market, then crossed Massanutten Mountain and captured the bridges across the South Fork in the Luray Valley, which Ashby’s cavalry had failed to destroy. This gave Banks control of the Shenandoah Valley as far south as Harrisonburg. |

| April 20 |

Banks assumed Jackson was leaving the Valley to reinforce Confederate forces around Richmone and suggested that he should follow with his men. Instead, Lincoln ordered him to transfer Shields’ Division to McDowell at Fredericksburg and Banks to withdraw his remaining division to Strasburg and take up a defensive position. Confederate General Joseph Johnston ordered Jackson to stop Banks from taking Staunton and threatening the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad. He also ordered the 8,500 man division of Richard Ewell to move from Brandy Station, where it was covering Johnston’s far left flank, and to reinforce Jackson. |

| April 21 | Jackson received a letter from Robert E. Lee, who was then serving as military advisor to President Jefferson Davis, asking Jackson to attack Banks to reduce the threat against Richmond. |

| April 30 | Ewell’s division occupied Swift Run Gap, 10 miles east of Harrisonburg, while the rest of Jackson’s command marched to Port Republic. |

| May | |

| May 2 | Jackson marched east towards Charlottesville, leaving the Shenandoah Valley, apparently heading toward Richmond. |

| May 4 | Jackson’s men boarded trains that took them back to the west, returning to the Valley and disembarking at Staunton. They joined with Edward Johnson’s Brigade, which had been slowing the advance of Union General Robert Milroy, part of Fremont’s command in western Virginia. |

| May 7 | Jackson moved west out of Staunton and West View on the Parkersburg Turnpike. Edward Johnson’s Brigade led the way. Milroy’s Union forces at Rodger’s Tollgate withdrew to the crest of Shenandoah Mountain and then to McDowell. |

| May 8 |

Battle of McDowellRobert Schenck reached McDowell after a forced march from Franklin and took command from Milroy. A midafternoon Union attack failed to break the Confederate line and withdrew at darkness. Schenck then pulled out of McDowell toward Franklin. He had inflicted more casualties on Jackson than he had lost, but was forced to withdraw, leaving Jackson the freedom of manoever for the next stage of his campaign. |

| May 9-15 | Jackson pursued Schenck toward Franklin. |

| May 10 | Thinking Jackson was no longer a threat and concerned about the ability to supply Banks’ men so far south in the Valley, Lincoln ordered Banks to transfer Shield’s Division to McDowell’s Department of the Rappahannock, retreat to Strasburg and go on the defensive. |

| May 16-20 | Jackson returned to New Market. |

| May 21-22 | Jackson sent Ashby’s cavalry north from New Market to threaten Banks at Strasburg, while he moved the rest of his forces into the Luray Valley and joined up with the division of Major General Richard Ewell. |

| May 23 |

Battle of Front RoyalFront Royal was a Union outpost defended by 1,000 men of the First Maryland Infantry Regiment under the command of Colonel John R. Kenly. It was on the south side of the confluence of the South and North Forks of the Shenandoah River, meaning their line of retreated required them to cross two long bridges. Jackson had learned that Maryland troops held Front Royal, and chose the Confederate First Maryland Infantry Regiment, bitter enemies of Kenly’s men, to lead the attack. At about 2 p.m. he moved rapidly into Front Royal, sweeping small Union detatchments ahead of him, while Kenly made a stand on a hill north of town. Jackson was about to attack them when Kenly saw Ashby’s cavalry approaching the bridges on his escape route. Kenly quickly abandoned his position and moved North over the bridges, setting fire to them as they passed. They were pursued by Taylor’s Louisiana Infantry brigade and a detachment of the 6th Virginia Cavalry Regiment that forced Kenly’s men to make a stand at Cedarville, two miles north of the river crossing. The first cavalry charge broke the Union line and it reformed, while the second overran and routed them. Kenly’s forced was almost wiped out, losing 773 men, of whom 691 were captured. Jackson lost 36 men killed and wounded. He also captured hundreds of thousands of dollars of supplies. Two Union guns belonging to Pennsylvania Independent Battery E had to be spiked and abandoned, although they were recovered later. |

| May 24 |

Banks at first believed the attack on Front Royal to be a feint and did not want to withdraw from Strasbug. But he realized that he had been outflanked and Jackson – who outnumbered him at this point – could potentially reach Winchester before him and cut off his line of retreat. At 3 a.m. he sent off a wagon train with his sick and wounded, and started his infantry North at midmorning. Jackson ordered Ewell’s division north along the road to Winchester, but not to get too far ahead in case Banks decided to cut due east and escape the Valley altogether. He also sent some of Ewell’s cavalry to Newton to try to intercept Banks’ column if it did go to Winchester. Ewell’s cavalry reported back that Banks was indeed moving north, and Jackson started his main force toward Middletown. They fought their way through a screen of Union cavalry and in mid-afternoon started shelling the Union column. The Louisiana Tigers charged the Union wagon train and began looting until around 4 p.m., when Union infantry arrived. By the time Jackson’s men had formed up to attack the Federals had gone, and Jackson realized that he was dealing with the rearguard of Banks’ column and not the middle. They began a pursuit of the Union column, which was slowed after Ashby’s cavalry had looted the wagon train and many had gotten drunk. Pursuit continued until after dark, when the exhausred men were allowed two hours sleep. That afternoon President Lincoln ordered Major General Irvin McDowell to detach 20,000 men from his First Corps to reinforce Banks. These were men who had been intended to advance on Richmond from the north in aid of McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign. McClellan considered their loss to Banks a betrayal which further soured relations between him and Lincoln and Stanton in Washington. |

| May 25 |

Battle of WinchesterBanks had formed a defensive line just south of Winchester anchored on Bower’s Hill, hoping to delay Jackson long enough to allow his slow moving wagons to reach safety. Jackson attacked at dawn and in a three-hour battle broke the Union lines and sent Banks’ men flying. A quarter of Banks’ army became casualties. But Jackson praised the Union troops in their withdrawal, writing that they “preserved their organization remarkably well.” Jackson’s vistory was incomplete. His cavalry was not on the field, Ashby having led them away from the main battle to chase a Union detachment. Jackson missed them, writing “Never was there such a chance for cavalry. Oh that my cavalry was in place!” His exhausted infantry was unable to pursue, and in 14 hours Banks’ army had reached safety across the Potomac. But he had lost over 2,000 men, most of them captured, while Jackson suffered 400 casualties. |

| May 26 |

Robert E. Lee had urged Jackson to push his army up to threaten the Potomac. Jackson learned that Shirlds’ Union division was returning from Fredericksburg. Lincoln’s plan was to trap Jackson between three Union forces: Shields moving in from the east and Fremont moving in from the west to meet between Strasburg and Front Royal, while Banks recrossed the Potomac and drove Jackson to the south from behind. |

| May 28-29 | Most of Jackson’s forces camped at Charlestown, while he ordered the Stonewall Brigade to threaten Harpers Ferry. |

| May 30 | Sheilds recaptured Front Royal, threatening Jackson’s line of retreat. Jackson began withdrawing back to Winchester. |

| June | |

| June 1 |

Banks decided his army was not recovered from their defeats and would not be able to pursue. Fremont was delayed by bad roads (while Jackson was moving swiftly on the paved Valley Pike) and Shields would not move from Front Royal until Ord’s division reinforced him. Most of Jackson’s force had escaped the trap, leaving only the Stonewall Brigade who had to march all the way extra to Harpers Ferry. Jackson waited where the pincers were to come together until the fast moving “foot cavalry” of the Stonewall Brigade came into sight just after noon. |

| June 2-5 | Fremont pursued up the main valley while McDowell moved up Luray Valley on the east side of Masanutton Mountain. Jackson’s men covered 40 miles in 36-hours along the Valley Pike, There were frequent cavalry skirmishes as Ashby’s cavalry delayed the Union columns. |

| June 6 |

Battle of HarrisonburgIn the evening the 13th Pennsylvania Reserves Regiment (Pennsylvania Bucktails) under the command of Colonel Thomas Kane fought on heavily wooded Chestnut Ridge about a mile and a half east of Harrisonburg with the 58th Virginia Infantry Regiment under Colonel Samuel H. Letcher, the 1st Maryland Infantry Regiment commanded by Colonel Bradley Johnson, and the 7th Virginia Cavalry Regiment under Colonel Turner Ashby. Ashby was killed and Colonel Kane captured in a hard fight and the Pennsylvanians were driven off. Ashby had been appointed Brigadier General, but the Confederate Semate had not yet approved the appointment. |

| June 7 |

Jackson wanted to keep Fremont and Shields from joining together, then defeat each of them independently. He carefully chose terrain at Port Republic where two branches of the South Fork of the Shenandoah River came together. Jackson controlled the crossings, with Fremont and Shields on opposite sides. He ordered Ewell to take up a strong position on a ridge at Cross Keys, an invitation for Fremont to attack. Fremont thought he was outnumbered. But Taylor’s brigade had been detached from Ewell and was with Jackson, so Fremont outnumbered Ewell by two to one. |

| June 8 |

Battle of Cross KeysFremont moved up cautiously, then launched an ineffective artillery barrage. Stahel’s Union brigade then cleared away North Carolina skirmishers while moving across a clearing and up a hill, only to run into intense fire that caused almost 40% casualties in the 8th New York Infantry Regiment. Fremont then launched a series of small, ineffective attacks against Ewell’s line before eventually withdrawing his men. Ewell decided not to counterattack, knowing he was badly outnumbered. Fremont lost 685 men and Ewell only 288, although Confederate Brigadier Generals Arnold Elzey and George Steuart were badly wounded. |

| June 9 |

Battle of Port RepublicWith Fremont out of the picture Jackson could now concentrate against Shields. Jackson left behind a token force to cover Fremont and ordered the majority of Ewell’s men across the South Fork to join the rest of his army. He advanced until he encountered Shield’s leading units, two brigades under the command of Brigadier General Erastus Tyler. The rest of Shield’s Division was stretched out over 35 miles of muddy roads back to Luray and would not take part. Jackson would have about 6,000 men against about 3,500 Federals. Jackson opened the battle by sending the Stonewall Brige in a charge into the fog without proper reconnaissance or support. They were surprised to run into two Union brigades supported with artilley and were thrown back in confusion. The Union artillery was placed in a strong position on a ridge called “the Coaling.” Jackson sent two Virginia regiments into the thick underbrush to drive them out, but they were driven back by three Union regiments. While waiting for Ewell’s men to cross the river and join him Jackson launched another attack against the Union line. The Stonewall Brigade, reinforced by the 7th Louisiana Infantry Regiment, was stopped by intense rifle fire and, running low on ammunition, was routed. The 7th Louisiana lost 50% of its men. The Union line then advanced, but was forced to withdraw. Taylor’s Louisiana Brigade attacked the Coaling twice more. He finally took it, capturing five guns and flanking the Union line. More of Ewell’s Division arrived as reinforcements, and Tyler reluctantly began to withdraw. Jackson lost 816 men against 1,000 Federals, with many of the Federal casualties being captured. It was not a good showing for Jackson’s army, which outnumbered Tyler almost two to one. The lack of reconnaissance was costly – these were Jackson’s first battles without his cavalry commander, Turner Ashby. So were Jackson’s repeated use of frontal attacks against well-led troops in strong positions. Was he spoiled from having faced so many poorly trained and poorly led enemies? |

| June 10-18: Aftermath |

Fremont withdrew and united with Banks and Sigel at Middletown. Shields withdrew to Front Royal and then left the Valley to join McDowell at Fredericksburg.. Jackson asked for reinforcements that would bring his army up to 40,000 men so he could clear the Shenandoah Valley of Union troops, cross the Potomac and march on Washington. Lee sent him 14,000 men, but revealed his plan for Jackson to bring his army to Richmond to attack McClellan’s right flank. After Midnight on June 18 the Valley Army crossed the Blue Ridge for Richmond. |