Campaign Overview * Campaign Timeline

The Gettysburg Campaign was fought in June and July of 1863. It began along the Rappahannock River in Virginia and extended as far as the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania, a distance of almost 200 miles as some of the Confederate forces marched. The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia under the command of General Robert E. Lee faced the Federal Army of the Potomac under Major General Joseph Hooker, who was replaced in mid-campaign by Major General George Meade. The Army of the Potomac was also reinforced by toops from the Washington defences and militia from the newly established Department of the Susquehanna.

Strategic Situation, May 1863

By the end of May 1863 the Civil War had been raging for two years. It had another two years to go and was at its halfway point, although no one knew it at the time. Most of the Mississippi River was in Union hands, including New Orleans, the Confederacy’s largest city. Ulysses Grant’s Army of the Tennessee had encircled the last Southern strong point on the river at Vicksburg and begun a siege that threatened to cut the Confederacy in two. William Rosecran’s Federal Army of the Cumberland was clearing Confederate forces out of Tennessee and threatened the strategic Confederate rail center of Chattanooga.

In Virginia Joseph Hooker’s Union Army of the Potomac faced Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia across the Rappahannock River. Twice the North had tried to force their way across the river and clear the road for the final 50 miles to Richmond. Both attempts failed.

Fredericksburg had been a bloodbath for the Union, who lost twice the casualties as the South. Chancellorsville was even more costly for the North, in spite of the fact that 20,000 Confederates under Longstreet had been detached for an expedition to Southern Virginia that gave Hooker an almost two to one advantage over Lee. But Lee had lost “Stonewall” Jackson, the man behind Lee’s stunning victory, mortally wounded by his own men. Lee was also frustrated. Both victories were hollow to him since afterwards the Union army had been able to retreat back across the river to safety where Lee could not easily follow.

Confederate Objectives

There were suggestions that Lee send part of his army west, or even go himself, to stop Grant at Vicksburg. But Lee resisted any plans that would reduce his army or take him away from Virginia, his native state. Instead Lee developed a plan that would maneuver the Union forces in the east out in the open where a Confederate victory would allow him to pursue and destroy the defeated Union army. It would move the fighting into Union territory where he could collect badly needed supplies for his army. It would remove Union forces from Virginia, giving Confederate farmers a chance to plant and harvest crops. And a victory would hopefully distract Grant from his campaign against Vicksburg and possibly even force the North to divert troops back to the east. At its best, the plan could see Lee capture a major Northern city such as Baltimore or Philadelphia – perhaps even Washington itself – and the possible end of the war.

Union Objectives

The Union plan was much simpler. Hooker would try to damage Lee while keeping in between his army and Washington. It’s goal was not territory, but Lee’s army itself. Hooker would have the advantage of fighting on his own territory with shorter supply lines, easier access to reinforcements, and surrounded by a sympathetic civilian population.

The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia (see organization)

Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia went through a major reorganization in the month between Chancellorsville and Gettysburg due to the loss of Second Corps commander Thomas Jackson. The Third Corps was created by taking a division each from the First and Second Corps and forming a new division. Lee’s artillery was reorganized, removed from the control of individual brigades and placed in artillery battalions. Each of the three corps would be assigned five artillery battalions, with one assigned to each division and two battalions held in a corps artillery reserve. There was also a battalion of horse artillery assigned to Stuart’s cavalry.

Three additional cavalry brigades were also brought in from North Carolina and western Virginia and added to Stuart’s Cavalry Division.

The new structure gave Lee a balanced organization of three infantry corps. Each had three infantry divisions and two reserve artillery battalions. There was also a cavalry division with seven brigades of cavalry and horse artillery.

The new Third Corps would be commanded by the former senior Second Corps division commander, A.P. Hill. The Second Corps would be led by another former Second Corps division commander, Richard Ewell. Longstreet’s First Corps gave up Anderson’s Division to the Third Corps, and it was hoped that the Longstreet’s men would continue their reputation as the strong knock-out punch of the army. The Second Corps would hopefully continue its reputation as Jackson’s swift-moving “foot cavalry”. The Third Corps was as yet an unknown quantity, but there were high hopes that with a division from each of the army’s two original corps that it might be the best of both worlds.

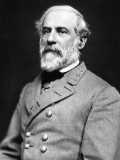

Confederate Commanders

General Robert Edward Lee had been Winfield Scott’s top engineer officer during the march to Mexico City during the Mexican War. After joining the Confederacy he had commanded an unsuccessful campaign in west Virginia and then had worked on defences along the Carolina coast before becoming military advisor to President Jefferson Davis. He took command of the Army of Northern Virginia on June 1, 1862 after General Joseph Johnson was wounded.

General Robert Edward Lee had been Winfield Scott’s top engineer officer during the march to Mexico City during the Mexican War. After joining the Confederacy he had commanded an unsuccessful campaign in west Virginia and then had worked on defences along the Carolina coast before becoming military advisor to President Jefferson Davis. He took command of the Army of Northern Virginia on June 1, 1862 after General Joseph Johnson was wounded.

He led it through several brilliant campaigns, taking it in a year from a desperate defense at the gates of Richmond to an invasion of the North that threatened Washington D.C. Always fighting against superior numbers, Lee relied on initiative, speed, audacity, and the qualities of his troops, whom he felt had no equal.

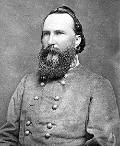

Lieutenant General James Longstreet had been a senior division commander in the early days of the army. The Confederate Congress had not authorized corps or the rank of lieutenant general. So Longstreet as senior division commander was assigned several subordinate division commanders, creating an improvised corps structure. When the Congress approved the structure and rank in the fall of 1862 Longstreet was promoted to Lieutenant General and his collaction of divisions became the First Corps.

Lieutenant General James Longstreet had been a senior division commander in the early days of the army. The Confederate Congress had not authorized corps or the rank of lieutenant general. So Longstreet as senior division commander was assigned several subordinate division commanders, creating an improvised corps structure. When the Congress approved the structure and rank in the fall of 1862 Longstreet was promoted to Lieutenant General and his collaction of divisions became the First Corps.

He was known for being slow and deliberate, but also for delivering crushing attacks as in the Second Battle of Manassas. Lee called him “my old war horse” and relied heavily on him, especially after the death of Jackson.

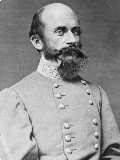

Lieutenant General Richard Ewell had been a division commander under Jackson until badly wounded at Brawner’s Farm on August 28, 1862, where he lost his leg. After almost a year, he recovered in time to be chosen to command the Second Corps after Jackson died from his Chancellorsville wound.

Lieutenant General Richard Ewell had been a division commander under Jackson until badly wounded at Brawner’s Farm on August 28, 1862, where he lost his leg. After almost a year, he recovered in time to be chosen to command the Second Corps after Jackson died from his Chancellorsville wound.

Ewell had been Jackson’s senior subordinate during the legendary Valley Campaign, and it was hoped that Ewell had picked up some of Jackson’s magic. If anything, he almost matched Jackson in his many eccentricities. It helped that one of the Second Corps divisions was Ewell’s old division and knew him well. Still, Ewell had big shoes to fill, and the Gettysburg Campaign would be his first big test.

Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell Hill had been an outstanding division commander of what had been the largest division in the Confederate army. His difficulty was dealing with his commanding officers. He fought with Longstreet to the point where he challenged him to a duel. After his division was transferred to Jackson he again quarreled frequently and was often under arrest. He was also frequently sick, a mysterious recurring illness that sometimes sidelined him at inopportune times.

Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell Hill had been an outstanding division commander of what had been the largest division in the Confederate army. His difficulty was dealing with his commanding officers. He fought with Longstreet to the point where he challenged him to a duel. After his division was transferred to Jackson he again quarreled frequently and was often under arrest. He was also frequently sick, a mysterious recurring illness that sometimes sidelined him at inopportune times.

Still, his forced march from Harpers Ferry and attack on Burnside at Sharpsburg (Antietam) saved Lee’s flank, and probably the battle. Giving Hill the Army of Northern Virginia’s newest corps was a gamble for Lee, but he felt that Hill was the best qualified officer for the job.

Major General James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart had built up the Confederacy’s cavalry arm since the beginning of the war, and by the start of the Gettysburg Campaign commanded a division of seven brigades. It was universally regarded that Stuart’s cavalry was far superior to the Union horsemen. He had also shown his versatility when he temporarily stepped into command of the Second Corps at Chancellorsville after Jackson was wounded. Historian Jeffrey Wert described him as “Confederacy’s knight-errant,” known for his cape and plume and being accompanied by his personal banjo player. But behind the show was solid ability that served Lee as the eyes and ears of the army.

Major General James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart had built up the Confederacy’s cavalry arm since the beginning of the war, and by the start of the Gettysburg Campaign commanded a division of seven brigades. It was universally regarded that Stuart’s cavalry was far superior to the Union horsemen. He had also shown his versatility when he temporarily stepped into command of the Second Corps at Chancellorsville after Jackson was wounded. Historian Jeffrey Wert described him as “Confederacy’s knight-errant,” known for his cape and plume and being accompanied by his personal banjo player. But behind the show was solid ability that served Lee as the eyes and ears of the army.

The Federal Army of the Potomac (see organization)

Joseph Hooker’s Army of the Potomac also went through considerable reorganization as 30 regiments mustered out at the end of their enlistments after Chancellorsville. Whole brigades were dissolved.

To make up for these missing men reinforcements were added from the Washington Defences. Two brigades of veteran Pennsylvania Reserves that had been recovering from heavy casualties returned to the army, along with two brigades of cavalry and a brigade of untried Vermont troops who would fight like veterans when the time came.

The Army of the Potomac’s artillery was also reorganized. The infantry divisions’ artillery were reallocated to artillery brigades attached to each infantry corps, two brigades of horse artillery were attached to the cavalry corps, and six brigades were formed into an army artillery reserve.

Union Commanders

Major General Joseph Hooker made a reputation for himself as an aggressive division commander who was devoted to the welfare of his men. He was also a hard drinking ladies’ man that despised his superiors. Hooker believed he was a better general than McClellan and Burnside, and was not afraid to let everyone else know. Hooker got his chance to prove it when Burnside was removed and he took over the Army of the Potomac in January of 1863. To the surprise of many he did an excellent job as an administrator rebuilding the army. He restored morale by reforming the army’s diet, sanitary arrangements, and furlough system. He introduced the system of corps badges to build esprit de’ corps. He created the Bureau of Military Information, an intelligence service which provided excellent service until the end of the war. And he combined all of the army’s cavalry into a single corps. He even came up with a good plan to outflank Lee’s defensive lines at Fredericksburg and punch through to Richmond. Unfortunately, he fumbled while executing his plan, giving Lee one of his greatest victories and losing a great deal of the goodwill he had begun to build up with the army and the administration.

Major General Joseph Hooker made a reputation for himself as an aggressive division commander who was devoted to the welfare of his men. He was also a hard drinking ladies’ man that despised his superiors. Hooker believed he was a better general than McClellan and Burnside, and was not afraid to let everyone else know. Hooker got his chance to prove it when Burnside was removed and he took over the Army of the Potomac in January of 1863. To the surprise of many he did an excellent job as an administrator rebuilding the army. He restored morale by reforming the army’s diet, sanitary arrangements, and furlough system. He introduced the system of corps badges to build esprit de’ corps. He created the Bureau of Military Information, an intelligence service which provided excellent service until the end of the war. And he combined all of the army’s cavalry into a single corps. He even came up with a good plan to outflank Lee’s defensive lines at Fredericksburg and punch through to Richmond. Unfortunately, he fumbled while executing his plan, giving Lee one of his greatest victories and losing a great deal of the goodwill he had begun to build up with the army and the administration.

Major General George Gordon Mead was the commander of the Fifth Corps when Hooker was abruptly relieved on June 28 and Meade was ordered to take over of the army.

Major General George Gordon Mead was the commander of the Fifth Corps when Hooker was abruptly relieved on June 28 and Meade was ordered to take over of the army.

Meade had been a brigade commander in the Pennsylvania Reserves Division and commanded the division before being promoted to corps command. An engineer, he was a steady, competent officer, His was the only division to break the Confederate line at Fredericksburg. But he had a terrible temper which along with his spectacles earned him the description as an “old goggle eyed snapping turtle.”

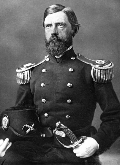

Major General John Reynolds also commanded a brigade in the Pennsylvania Reserves at the beginning of the war. He briefly served as military governor of Fredericksburg, where he was praised by local citizens. Captured at Gaines’s Mill, he spent several weeks in Libby Prison in Richmond but was quickly exchanged and took command of the entire Pennsylvania Reserves Division. In the rearguard at Second Manassas he led a counterattack that successfully covered the withdrawal of Pope’s army. He was sidelined during the Maryland Campaign because Governor Curtin of Pennsylvania wanted a veteran general to command militia troops in Pennsylvania during Lee’s invasion.

Major General John Reynolds also commanded a brigade in the Pennsylvania Reserves at the beginning of the war. He briefly served as military governor of Fredericksburg, where he was praised by local citizens. Captured at Gaines’s Mill, he spent several weeks in Libby Prison in Richmond but was quickly exchanged and took command of the entire Pennsylvania Reserves Division. In the rearguard at Second Manassas he led a counterattack that successfully covered the withdrawal of Pope’s army. He was sidelined during the Maryland Campaign because Governor Curtin of Pennsylvania wanted a veteran general to command militia troops in Pennsylvania during Lee’s invasion.

Reynolds returned to the army in time for Fredericksburg and was given command of the First Corps, where one of his divisions under George Meade made the only breakthrough in the Confederate lines. At Chancellorsville Reynold’s First Corps was not engaged, to his disgust.

Major General Wifrield Scott Hancock was the newest corps commander in the army, having replaced Darius Couch at the end of May when Couch resigned after an argument with Hooker.

Major General Wifrield Scott Hancock was the newest corps commander in the army, having replaced Darius Couch at the end of May when Couch resigned after an argument with Hooker.

In Mexico Hancock had been breveted for gallantry and had been wounded. At the start of the Civil War he was promoted to brigadier general. Hancock gained an outstanding reputation as a brigade commander in the Peninsula. McClellan himself described him as “Hancock the superb” for his counterattack at the Battle of Williamsburg. He habit was to lead from the front, and Hancock was wounded at both Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. Hancock was also famous both for his profanity and for somehow always wearing a crisp, clean white shirt.

Major General Daniel Sickles was the only corps commander in the army who was not a West Pointer. He was a scandal-plagued congressman who shot and killed his wife’s lover across the street from the White House, then scandalized the public even more when he forgave his wife and took her back. At the start of the Civil War he raised the Excelsior Brigade, and was appointed Colonel of one of its four regiments. He was a staunch abolitionist, refusing to return escaped slaves to their owners and hiring many as servants. Sickles was soon promoted to brigadier general of the Excelsior Brigade. His opponents in Congress refused to confirm his commission, but after two months of lobbying he was finally confirmed.

Major General Daniel Sickles was the only corps commander in the army who was not a West Pointer. He was a scandal-plagued congressman who shot and killed his wife’s lover across the street from the White House, then scandalized the public even more when he forgave his wife and took her back. At the start of the Civil War he raised the Excelsior Brigade, and was appointed Colonel of one of its four regiments. He was a staunch abolitionist, refusing to return escaped slaves to their owners and hiring many as servants. Sickles was soon promoted to brigadier general of the Excelsior Brigade. His opponents in Congress refused to confirm his commission, but after two months of lobbying he was finally confirmed.

Sickles surprisingly proved himself to be a competent brigade commander in the Peninsula Campaign. He was helped by his strong political connections with Tammany Hall and his close friendship with Hooker, who had been his original division commander. Both were hard drinking ladies’ men. By fall he was promoted to division command , and in February of 1863 Hooker gave him command of the Third Corps.

Major General John Sedgwick was the next to senior corps commander in the army. Sedgwick had fought in Mexico and in the Indian Wars, serving at first in the infantry and then commanding a battery of artillery before becoming a major in the First Cavalry Regiment under Colonel Robert E. Lee. Shortly after the beginning of the Civil War Sedgwick was promoted to brigadier general. He was then promoted to division command in Sumner’s Second Corps, and was wounded at Glendale. At Antietam Sumners ordered Sedgwick’s division into a disastrous mass advance on the East Woods. Attacked on three sides, Sedgwick lost half his men in a matter of minutes, and was wounded three times himself and carried from the field unconscious.

Major General John Sedgwick was the next to senior corps commander in the army. Sedgwick had fought in Mexico and in the Indian Wars, serving at first in the infantry and then commanding a battery of artillery before becoming a major in the First Cavalry Regiment under Colonel Robert E. Lee. Shortly after the beginning of the Civil War Sedgwick was promoted to brigadier general. He was then promoted to division command in Sumner’s Second Corps, and was wounded at Glendale. At Antietam Sumners ordered Sedgwick’s division into a disastrous mass advance on the East Woods. Attacked on three sides, Sedgwick lost half his men in a matter of minutes, and was wounded three times himself and carried from the field unconscious.

Sedgwick didn’t return to the army until after Fredericksburg. He briefly commanded the Ninth Corps before transferring to command of the Sixth Corps a few weeks later. During the Chancellorsville Campaign Sedgwik had a semi-independent role, continuing to threaten the Confederate troops at Fredericksburg while Hooker took most of the army on a flank march. He then crossed the Rappahannock and successfully stormed Marye’s Heights, then advanced west to take some of the pressure off Hooker after the collapse of the Eleventh Corps. This left Sedgwick’s Sixth Corps threatened with being surrounded by reinforcements which Lee was able to send. But Sedgwick was able to fight his way out of the trap and return to the north bank of the Rappahannock.

Major General Oliver O. Howard was teaching mathematics at West Point when the Civil War began. He resigned his commission as a lieutenant in Ordnance and was appointed Colonel of the 3rd Maine Infantry Regiment. He temporarily commanded his brigade at Bull Run (Manassas) and by fall was promoted to brigadier general and given permanent command of the brigade. Howard was badly wounded at Fair Oaks, losing his right arm. But he recovered in time for the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg) where he took over command of his division from the badly wounded John Sedgwick (see above).

Major General Oliver O. Howard was teaching mathematics at West Point when the Civil War began. He resigned his commission as a lieutenant in Ordnance and was appointed Colonel of the 3rd Maine Infantry Regiment. He temporarily commanded his brigade at Bull Run (Manassas) and by fall was promoted to brigadier general and given permanent command of the brigade. Howard was badly wounded at Fair Oaks, losing his right arm. But he recovered in time for the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg) where he took over command of his division from the badly wounded John Sedgwick (see above).

In April of 1863 he was took over command of the 11th Corps from Franz Sigel. Sigel, a Germany revolutionary, had been a poor general but a great recruiter. The many German speakers in the Eleventh Corps resented Howard, who had no ethnic ties, did not speak a word of German and seemed to look down at his immigrant troops. These bad feelings probably contributed to the poor performance and collapse of the Eleventh Corps at Chancellorsville, and things had only gotten worse by the start of the Gettysburg Campaign.

Major General Henry W. Slocum was the senior corps commander under Meade. After graduating from West Point he had served for four years with the artillery before resigning to become a lawyer. When the Civil War started he was appointed Colonel of the 27th New York Infantry Regiment. He was badly wounded at Bull Run but recovered and had capably risen through brigade and to division command. His division was complimented by Fitz-John Porter as “one of the best divisions in the Army.” During the Battle of South Mountain his division attacked defending Confederate defending high ground behind a stone wall and routed them, leading his commander, William B. Franklin, to say it was “the completest victory gained up to that time by any part of the Army of the Potomac.”

Major General Henry W. Slocum was the senior corps commander under Meade. After graduating from West Point he had served for four years with the artillery before resigning to become a lawyer. When the Civil War started he was appointed Colonel of the 27th New York Infantry Regiment. He was badly wounded at Bull Run but recovered and had capably risen through brigade and to division command. His division was complimented by Fitz-John Porter as “one of the best divisions in the Army.” During the Battle of South Mountain his division attacked defending Confederate defending high ground behind a stone wall and routed them, leading his commander, William B. Franklin, to say it was “the completest victory gained up to that time by any part of the Army of the Potomac.”

Slocum took over the Twelfth Corps after Antietam from the mortally wounded Joseph Mansfield. He did well at Chancellorsville, commanding not only his own corps but also the Fifth and Twelfth as part of the Right Wing. By seniority Slocum should have taken command of the army after Hooker resigned, but it was felt he was not aggressive enough, and Slocum agreed to serve under Meade, his junior in seniority.

Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton (promoted to Major General on June 22) had commanded a brigade of cavalry in the Peninsula. He took command of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Division in September of 1862. But McClellan never understood the role of cavalry, scattering his cavalry to various infantry divisions and using it as escorts for generals. Pleasonton was mostly an administrator, and had little opportunity to be recognized. He made up for this with heavy self-promotiion.

Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton (promoted to Major General on June 22) had commanded a brigade of cavalry in the Peninsula. He took command of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Division in September of 1862. But McClellan never understood the role of cavalry, scattering his cavalry to various infantry divisions and using it as escorts for generals. Pleasonton was mostly an administrator, and had little opportunity to be recognized. He made up for this with heavy self-promotiion.

When Hooker took over the army after Fredericksburg Stoneman was brought back to command the Cavalry Corps. But Stoneman was relieved after his poor performance at Chancellorsville. Pleasonton took command of the newly created Cavalry Corps, which concentrated all of the army’s cavalry under one officer for the first time. The Gettysburg Campaign was Pleasonton’s chance to make a name for himself and his cavalry.

Aftermath

By August both armies had returned to Virginia along the Rappahannock/Rapidan River line.

Lee brought back thousands of cattle, sheep and hogs collected from the rich Pennsylvania countryside. He also brought horses and mules to replace the army’s draft animals, tons of hay and grain and barrels of flour to feed them and his men, and the hundreds of wagons needed to carry it all. These spoils would provide several months of food for the army to augment the trickle of supplies the South was sending by this point in the war. The objective of collecting supplies from the enemy was a complete success.

But the Army of Northern Virginia had also left a great deal behind in Pennsylvania. It had suffered around 27,000 casualties, or around 40% of its total strength. Losses among field and company officers and NCOs were disproportionately high and would trouble the army for the rest of the war. The North had also lost heavily, around 30,000 men. But it was a smaller percentage of the total – about 32% – since they were a larger army. Many a Northern home would be visited by tragedy, but in the hard math of war the fact was the North could replace its losses more easily.

Lee had clearly lost, not just the battle, but his mystique of invincibility. Gettysburg showed that Lee could be beaten, although it took some time for everyone to realize it.

And the Gettysburg Campaign had not diverted a single Union soldier from Grant’s siege of Vicksburg. Vicksburg surrendered on July 4, even as Lee was readying his retreat from Gettysburg. It may have been the greatest failure of Lee’s campaign.