Chantilly Main Page * Battle of Chantilly * Ox Hill Battlefield Park * The Armies

Leaving the parking lot and walking counter clockwise along the loop of the Ox Hill Battlefield Park Interpretive Trail you will pass four wayside markers along the west side of the loop. All were erected in 2008 by the Fairfax County Park Authority.

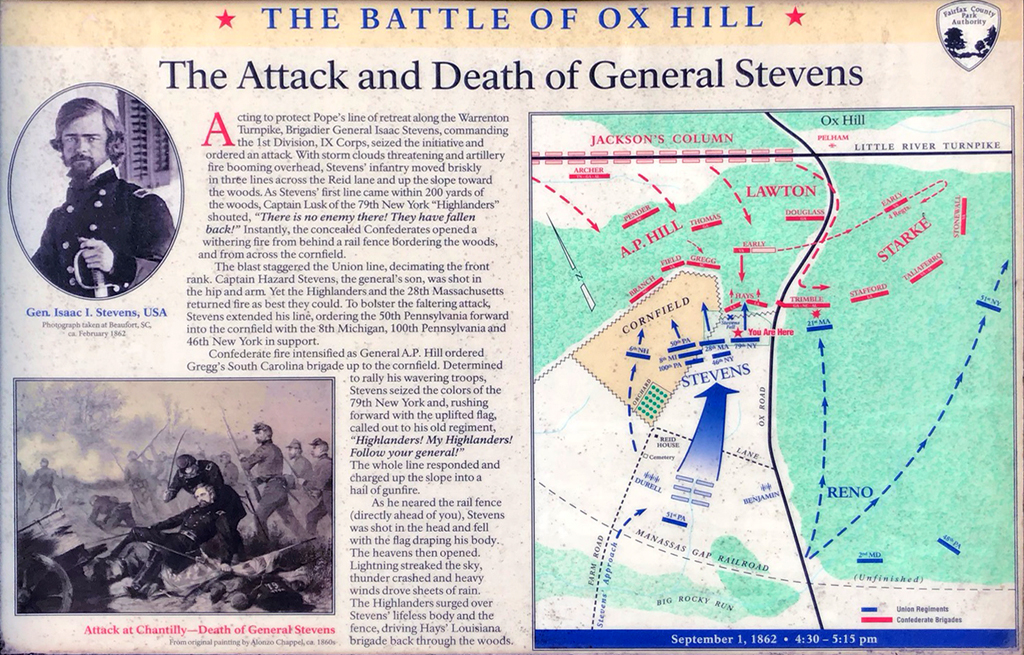

Attack and Death of General Stevens wayside marker

(First trail stop. Location: 38° 51.876′ N, 77° 22.228′ W)

Attack and Death of General Stevens

Acting to protect Pope’s line of retreat along the Warrenton Turnpike, Brigadier General Isaac Stevens, commanding the 1st Division, IX Corps, seized the initiative and ordered an attack. With storm clouds threatening and artillery fire booming overhead, Steven’s infantry moved briskly in three lines across the Reid lane and up the slope toward the woods. As Stevens’ first line came within 200 yards of the woods, Captain Lusk of the 79th New York “Highlanders” shouted, There is no enemy there! They have fallen back!” Instantly, the concealed Confederates opened a withering fire from behind a rail fence bordering the woods, and from across the cornfield.

The blast staggered the Union line, decimating the front rank. Captain Hazard Stevens, the general’s son, was shot in the hip and arm. Yet the Highlanders and the 28th Massachusetts returned fire as best they could. To bolster the faltering attack, Stevens extended his line, ordering the 50th Pennsylvania forward into the cornfield with the 8th Michigan, 100th Pennsylvania and 46th New York in support.

Confederate fire intensified as General A.P. Hill ordered Gregg’s South Carolina brigade up to the cornfield. Determined to rally his wavering troops, Stevens seized the colors of the 79th New York and, rushing forward with the uplifted flag, called out to his old regiment, “Highlanders! My Highlanders! Follow your general!” The whole line responded and charged up the slope into a hail of gunfire.

As he neared the rail fence (directly ahead of you), Stevens was shot in the head and fell with the flag draping his body. The heavens then opened. Lightning streaked the sky, thunder crashed and heavy winds drove sheets of rain. The Highlanders surged over Stevens’ lifeless body and the fence, driving Hays’ Louisiana brigade back through the woods.

Captions to photographs:

Gen. Isaac A. Stevens, USA

Photograph taken at Beaufort S.C.

ca. February 1962

Attack at Chantilly – Death of General Stevens

From Original Painting bt Alonzo Chappel ca. 1860s

The Battle of “Chantilly” (Ox Hill) — Then & Now wayside marker

(Second trail stop. Location: 38° 51.882′ N, 77° 22.248′ W.

The Battle of “Chantilly” (Ox Hill) — Then & Now

This early 20th-century photograph of the “Chantilly” battlefield was published by Fairfax County in 1907. The photo was taken from a vantage point a short distance ahead and to the right, beyond the park. It shows the pasture of the old Reid farm, at that time virtually unchanged since the day of the battle. The view today is unrecognizable.

The attack by General Isaac Stevens’ 1st Division, IX Corps came north across this pasture (toward you). In the foreground, the Union infantry was assailed by terrific volleys of Confederate musket fire coming from across the cornfield to your right and rear, and from the woods line to your left and rear where Monument Drive is today.

Call outs on the photograph (from left to right):

- West Ox Road

- Lane to the Reid (Ballard) House. (today Cedar Lakes Drive runs roughly parallel to, and about 150 feet north of, the original lane)

- Unfinished Manassas Gap Railroad. Marked by this distant tree line (old roadbed erased by Fair Lakes)

- Gen. Stevens formed his troops for attack in this field, just south of the lane to the Reid House (now part of Cedar Lakes and Fair Lakes)

- High ground west of the Millan House (present site of I-66 landfill, transfer station and recycling center)

- Reid (Ballard) House (demolished in 1965)–This fence crosses the path of the Union assault and was not there during the battle. Built in the post-war period, it runs through today’s Fairfield House condominiums on the left and Fair Ridge townhouses on the right.

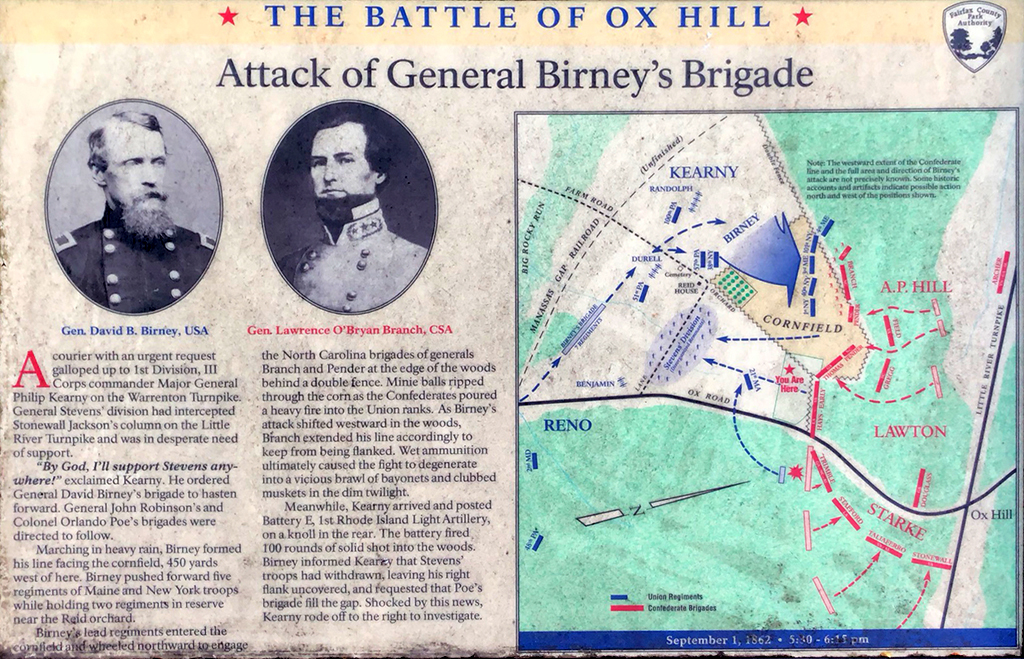

Attack of General Birney’s Brigade wayside marker

(Third trail stop. Location: 8° 51.883′ N, 77° 22.252′ W)

Attack of General Birney’s Brigade wayside marker

A courier with an urgent request galloped up to 1st Division, III Corps commander Major General Philip Kearny on the Warrenton Turnpike. General Stevens’ division had intercepted Stonewall Jackson’s column on the Little River Turnpike and was in desperate need of support.

“By God, I’ll support Stevens anywhere!” exclaimed Kearny. He ordered General David Birney’s brigade to hasten forward. General John Robinson’s and Colonel Orlando Poe’s brigades were directed to follow.

Marching in heavy rain, Birney formed his line facing the cornfield, 450 yards west of here. Birney pushed forward five regiments of Maine and New York troops while holding two regiments in reserve near the Reid orchard.

Birney’s lead regiments entered the cornfield and wheeled northward to engage the North Carolina brigades of generals Branch and Pender at the edge of the woods behind a double fence. Minie balls ripped through the corn as the Confederates poured a heavy fire into the Union ranks. As Birney’s attack shifted westward in the woods, Branch extended his line accordingly to keep from being flanked. Wet ammunition ultimately caused the fight to degenerate into a vicious brawl of bayonets and clubbed muskets in the dim twilight.

Meanwhile, Kearny arrived and posted Battery E, 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, on a knoll in the rear. The battery fired 100 rounds of solid shot into the woods. Birney informed Kearny that Stevens’ troops had withdrawn, leaving his right flank uncovered, and requested that Poe’s brigade fill the gap. Shocked by this news, Kearny rode off to the right to investigate.

Captions to the two portraits:

Gen David B. Birney, USA and Gen. Lawrence O’Bryan Branch, CSA.

Death of General Kearney wayside marker

(Fourth trail stop. Location: 38° 51.892′ N, 77° 22.256′ W)

Death of General Kearney

As a rainy darkness enveloped the battlefield, Major General Philip Kearny rode eastward to investigate the reported gap in the Union line. Reigning up in the pasture, Kearny became alarmed that Stevens’ division had abandoned that part of the field after being repulsed.

Finding remnants of the 21st Massachusetts, Kearny immediately ordered them into the cornfield to protect Birney’s flank. They protested that their ammunition was wet and the cornfield was full of rebels. Kearny vehemently disagreed. Under threats and denouncements, the regiment advanced as ordered but soon halted under fire after capturing two skirmishers from the 49th Georgia.

Incensed at this delay, Kearny prodded the regiment forward, saying they were firing on their own men and that no rebels were in the cornfield. When shown the two captives, Kearny responded impetuously, “Damn you and your prisoners!” Putting spurs to his horse, he galloped forward in the rain to reconnoiter. Entirely alone and wearing an India rubber cloak over his uniform, the one-armed general rode into the cornfield. Within 60 yards he encountered the line of the 49th Georgia. Realizing his mistake, Kearny wheeled around to flee.

In an instant there were cries of “That’s a Yankee officer!” “Surrender!” “Halt!” “Shoot him!” Kearny threw himself forward and dug in his spurs, but a dozen muskets flashed in the growing darkness. Kearny was shot from his horse and died instantly in the muddy cornfield.

Captions to photographs:

Gen. Philip Kearny, USA

Photograph taken at Washington, DC, March 1862.

Death of General Philip Kearny, September 1, 1862.

From The Century Magazine, ca. 1880s

The next morning, General Robert E. Lee sent Kearny’s body to the Union lines under a flag of truce.

The Death of General Kearny, Painting by Julian Scott, 1884.

Next stops:

Continue on the trail to the Virginia Historical Markers and Stevens & Kearney monuments.