The east Wall of the shelter shows the second set of displays of the Wilderness Battlefield Exhibit Shelter.

The east Wall of the shelter shows the second set of displays of the Wilderness Battlefield Exhibit Shelter.

The first panel of the east wall, The Battle of the Wilderness, gives a brief overview of the battle. The first panel of the east wall, The Battle of the Wilderness, gives a brief overview of the battle. The main part of the east wall talks about the two major parts of the battle, which were almost two unconnected fights.

The Battle of the Wilderness

On May 5, 1864, Lee moved swiftly eastward through Orange County and struck the Federals along two roads–the Orange Plank Road and the Orange Turnpike. Two bloody, largely separate battles exploded. They would evolve and eventually merge into a huge conflict that would engulf the Wilderness and consume thousands of lives.

Clash on the Orange Turnpike

“Clash on the Orange Turnpike” has two displays, Saunders Field and Confederate Flank Attack, about the struggle that occured in and around the clearing just outside the shelter.

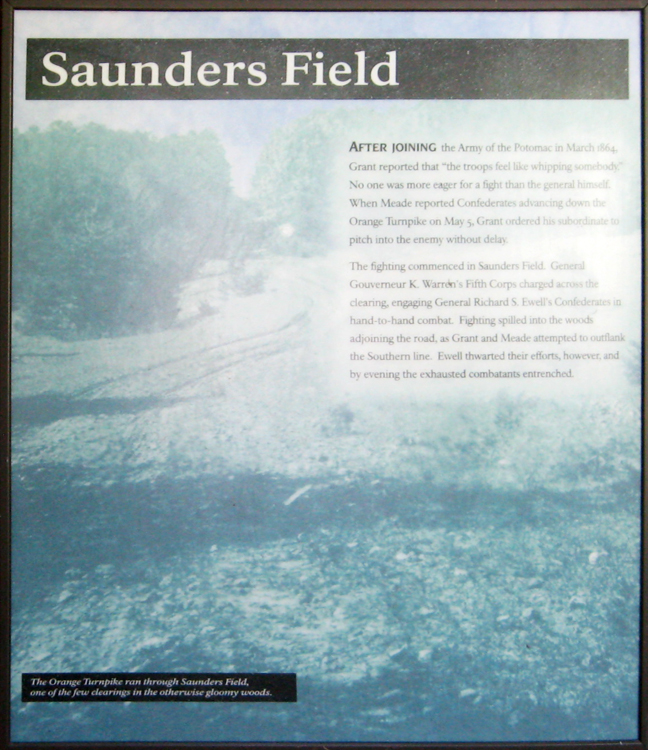

Saunders Field

After joining the Army of the Potomac in March 1864, Grant reported that “the troops feel like whipping somebody.” No one was more eager for a fight than the general himself. When Meade reported Confederates advancing down the Orange Turnpike on May 5, Grant ordered his subordinate to pitch into the enemy without delay.

The fighting commenced in Saunders Field. General Gouverneur K. Warren’s Fifth Corps charged across the clearing, engaging General Richard S. Ewell’s Confederates in hand-to-hand combat. Fighting spilled into the woods adjoining the road, as Grant and Meade attempted to outflank the Southern line. Ewell thwarted their efforts, however, and by evening the exhausted combatants entrenched.

Caption on the bottom of the photograph:

The Orange Turnpike ran through Saunders Field, one of the few clearings in the otherwise gloomy woods.

Confederate Flank Attack

May 6 was a comparatively peaceful day for Union soldiers on the Orange Turnpike. Following a brisk exchange of gunfire that morning, the fighting had tapered off. Now, as the sun dipped below the western horizon, Northern soldiers began to relax and prepare themselves dinner. Rifle fire in the woods north of the road interrupted their meal. Five thousand Confederates, led by General John B. Gordon, had taken position on the Union army’s right flank and were attacking.

Panic spread rapidly down the Union line. Two Federal generals and 800 other men fell captive. Nightfall and a stiffening Union defense, however, limited Gordon’s gains. Though battered, the Army of the Potomac ultimately took position in a new set of works, ensuring that the Battle of the Wilderness would end in stalemate.

Caption to the inset photo on the right:

General John B. Gordon who led the Confederate attack, “…Had the movement been made at an earlier hour and properly supported,” Gordon insisted, “…it would have resulted in a decided disorder to the whole right wing of General Grant’s army…”

Caption to the background drawing:

Artist Edwin Forbes sketched this picture of Sixth Corps soldiers fighting in the woods north of the Orange Turnpike. Gordon’s attack took the Sixth Corps by suprise and routed two of its brigades.

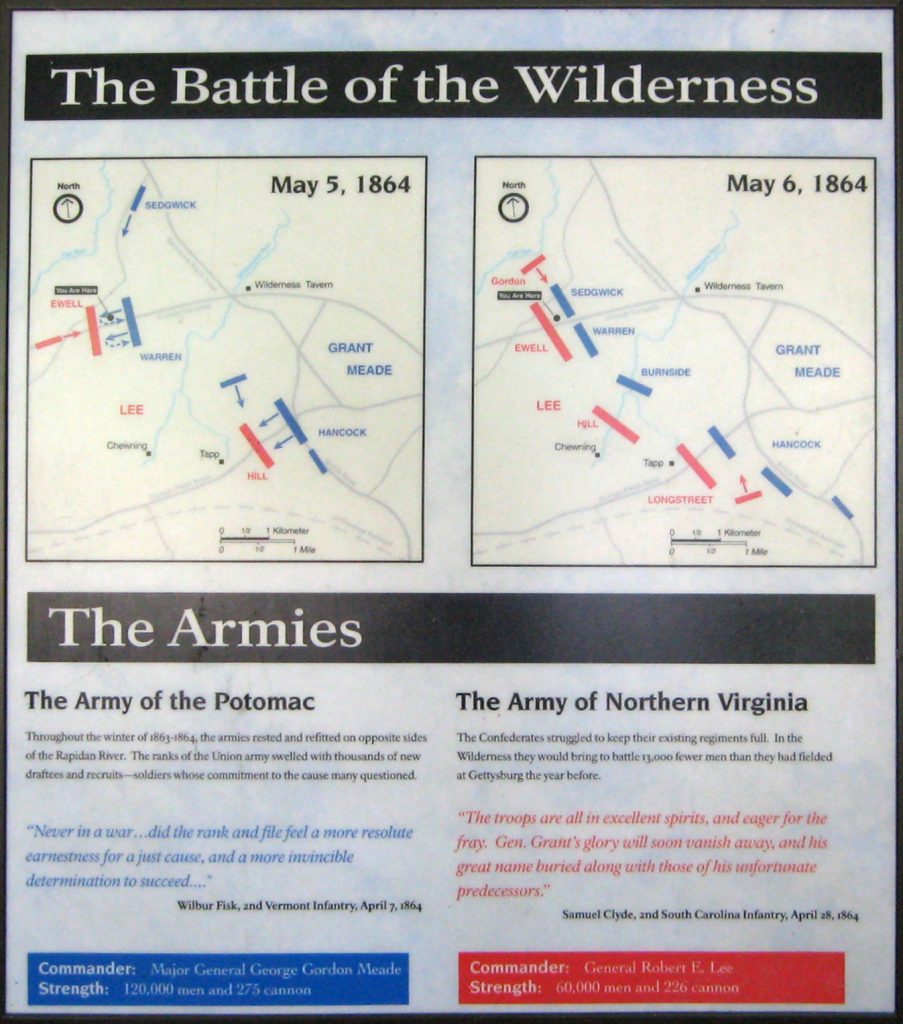

The center display shows maps of the two days of fighting

The middle panel, Battle of the Wilderness and The Armies, has tactical maps of the two days of the battle and a comparison of the armies.

The Battle of the WIlderness

The Armies

The Army of the Potomac

Throughout the winter of 1863-1864, the armies rested and refitted on opposites sides of the Rapidan River. The ranks of the Union army swelled with thousands of new draftees and recruits – soldiers whose commitment to the cause many questioned.

“Never in a war…did the rank and file feel a more resolute earnestness for a just cause, and a more invincible determination to succeed….”

Wilbur Fisk, 2nd Vermont Infantry, April 7, 1864

Commander: Major General George Gordon Meade

Strength: 120,000 men and 275 cannon

The Army of Northern Virginia

The Confederates struggled to keep their existing regiments full. In the Wilderness they would bring to the battle 13,000 fewer men than they had fielded at Gettysburg the year before.

“The troops are all in excellent spirits, and eager for the fray. Gen. Grant’s glory will soon vanish away, and his great name buried along with those of his unfortunate predecessors.”

Samuel Clyde, 2nd South Carolina Infantry, April 28, 1864

Commander: General Robert E. Lee

Strength: 60,000 men and 226 cannon

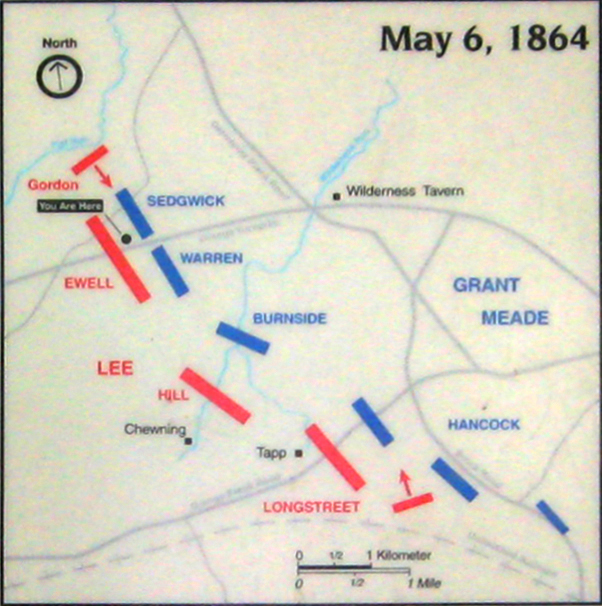

Closeup of the May 5 map

Closeup of the May 6 map

Clash on the Orange Turnpike

“Stuggle on the Orange Plank Road” tells of the fighting three miles to the southeast, with the Crisis at the Crossroads and Battle in the Balance displays.

Crisis at the Crossroads

Crises followed one after another on May 5. No sooner had Grant and Meade learned about Ewell’s approach on the Orange Turnpike than they discovered General A.P. Hill’s corps moving up the Orange Plank road. If Hill reached the Brock Road, he would cut the Army of the Potomac in two.

Union commanders rushed General Winfield S. Hancock’s Second Corps to the imperiled crossroads, securing it for the North. At 4 p.m., Hancock assailed Hill’s line. Fighting behind low logworks and amidst fires, Hill’s men stubbornly defended themselves against Hancock’s sledgehammer blows. When the fighting ended four hours later, Hill’s battered line was still intact.

“The wounded stream out, and fresh troops pour in. Stretchers pass with ghastly burdens, and go back reeking with blood for more.”

Reporter Charles Page, New York Tribune

Caption to the inset photo:

The Orange Plank Road witnessed two days of terrible combat.

Caption to the drawing:

Wadsworth’s division in the WIlderness

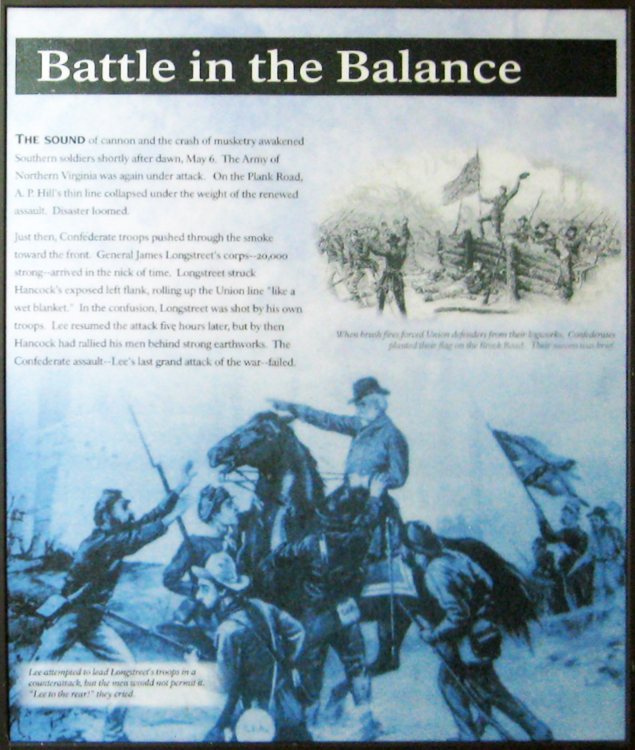

Battle in the Balance

The sound of cannon and the crash of musketry awakened Southern soldiers shortly after dawn, May 6. The Army of Northern Virginia was again under attack. On the Plank Road, A.P. Hill’s thin line collapsed under the weight of the renewed assault. Disaster loomed.

Just then, Confederate troops pushed through the smoke toward the front. General James Longtreet’s corps – 20,000 strong – arrived in the nick of time. Longstreet struck Hancock’s exposed left flank, rolling up the Union line “like a wet blanket.” In the confusion, Longstreet was shot by his own troops. Lee resumed the attack five hours later, but by then Hancock had rallied his men behind strong earthworks. The Confederate assault – Lee’s last grand attack of the war – failed.

Caption to the drawing at the bottom:

Lee attempted to lead Longstreet’s troops in a counterattack, but the men would not permit it “Lee to the rear!” they cried.

Caption to the drawing at the top right:

When brush fires forced Union defenders from their logworks, Confederates planted their flag on the Brock Road. Their success was brief.

(return to the main Exhibit Shelter page)

(return to the Stop 2 page)