Battle of the Wilderness • Tour the Battlefield • Monuments & Markers • The Armies

Longstreet’s Wounding is Stop 7 on the Wilderness Battlefield Auto Tour. It is on the south side of Orange Plank Road halfway between Hill-Ewell Drive and Brock Road.

Longstreet’s Wounding is Stop 7 on the Wilderness Battlefield Auto Tour. It is on the south side of Orange Plank Road halfway between Hill-Ewell Drive and Brock Road.

Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet was the senior officer in the Army of Northern Virginia after Robert E. Lee. He commanded the First Corps, about a third of the army, which had just returned to Virginia after several months in the Western Theater.

Longstreet’s arrival and counterattack on May 6 saved Lee’s army. But his wounding, so similar to the mortal wounding of Jackson the year before, was a serious blow to the army and to Lee. When Longstreet fell the Confederate counterattack stalled and allowed the Union troops to form a defensive line.

Longstreet would not return to the army until October, leaving Lee without his “warhorse” during the costly Overland Campaign which saw the Confederates battered back to the gates of Richmond.

There are three wayside markers at the Tour Stop:

Flank Attack (left), Burying the Dead (center), and Logstreet Felled (right) wayside markers at Tour Stop 7

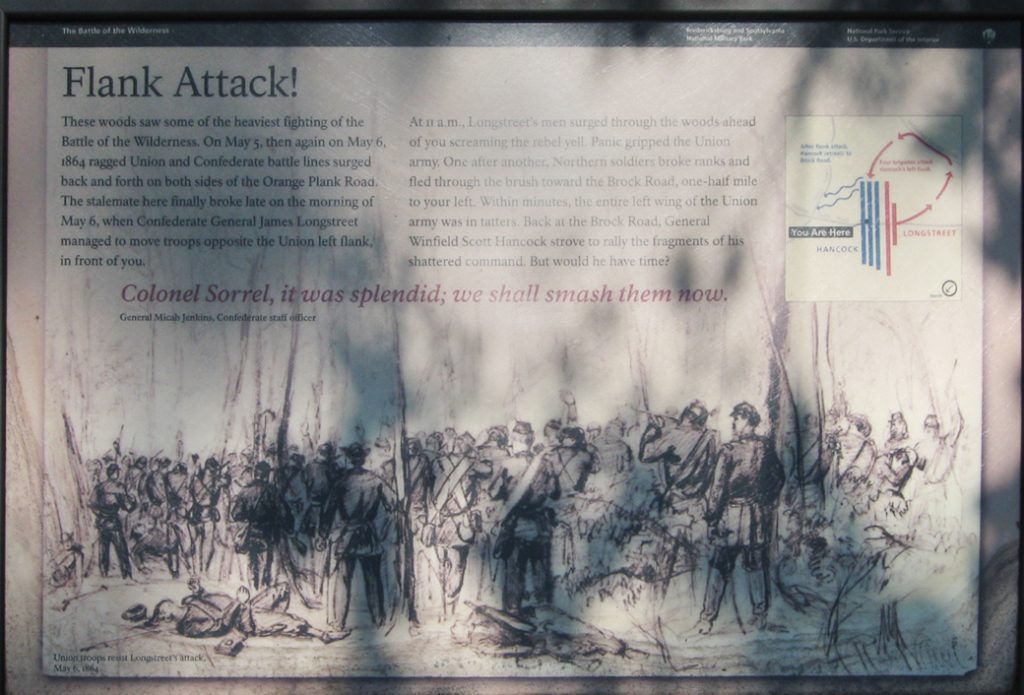

Flank Attack wayside marker

Text from the marker:

Flank Attack!

These woods saw some of the heaviest fighting of the Battle of the Wilderness. On May 5, then again on May 6, 1864 ragged Union and Confederate battle lines surged back and forth on both sides of the Orange Plank Road. The stalemate here finally broke late on the morning of May 6, when Confederate General James Longstreet managed to move troops opposite the Union left flank, in front of you.

At 11 a.m., Longstreet’s men surged through the woods ahead of you screaming the rebel yell. Panic gripped the Union army. One after another, Northern soldiers broke ranks and fled through the brush toward the Brock Road, one-half mile to your left. Within minutes, the entire left wing of the Union army was in tatters. Back at the Brock Road, General Winfield Scott Hancock strove to rally the fragments of his shattered command. But would he have time?

Colonel Sorrel, it was splendid; we shall smash them now.

General Micah Jenkins, Confederate staff officer*

Caption to the drawing:

Union troops resist Longstreet’s attack, May 6, 1864.

*Micah Jenkins is incorrectly noted on the marker as a staff officer. He commanded a brigade of South Carolina infantry in Field’s Division.

Longstreet Felled wayside marker

Text from the marker:

Longstreet Felled

It was the most successful day of James Longstreet’s career. He had arrived on the Wilderness battlefield early in the day to find the Confederate army in full retreat and in danger of being destroyed. His troops had prevented disaster. Now, at midday, he had just launched a flank attack that knocked the Union army back in confusion.

As Longstreet galloped down the road at the head of his victorious troops – near this spot – he inadvertently rode between two Confederate lines maneuvering in the dense roadside foliage. One of them fired a volley. A bullet struck Longstreet in the throat; another killed his subordinate Micah Jenkins, riding at his side.

Like “Stonewall” Jackson a year before, Longstreet had been felled by his own men. Unlike Jackson, Longstreet would survive. But his wounding here, on May 6, stalled the Confederate advance. By the time Lee was able to revive it, the opportunity for victory had passed.

…I shall not soon forget the sadness in [General Lee’s] face, and the almost despairing movement of his hands, when he was told that Longstreet had fallen.

Captain Francis W. Dawson, Longstreet’s staff

Caption to the background drawing:

This image portrays the moment of Longstreet’s wounding. Longstreet is at center; he would lose the use of his right arm for life.

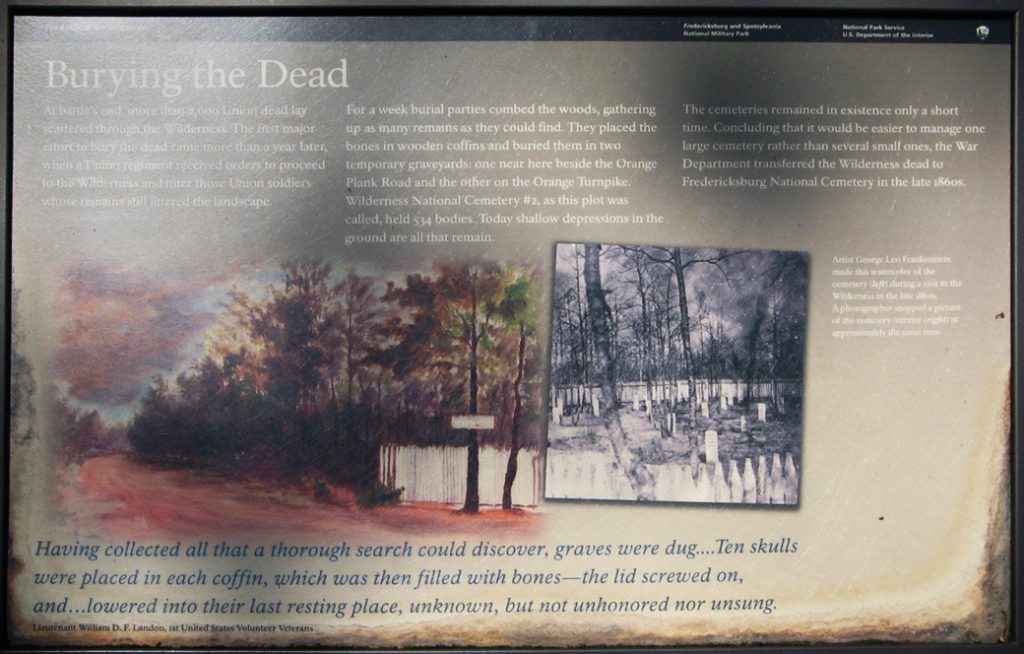

Burying the Dead wayside marker

Text from the marker:

Burying the Dead

At battles end, more than 2,000 Union dead lay scattered through the Wilderness. The first major effort to bury the dead came more than a year later, when a Union regiment received orders to proceed to the Wilderness and inter those Union soldiers whose remains still littered the landscape.

For a week burial parties combed the woods, gathering up as many remains as they could find. They placed the bones in wooden coffins and buried them in two temporary graveyards; one near here beside the Orange Plank Road and the other on the Orange Turnpike. Wilderness National Cemetery #2, as this plot was called, held 534 bodies. Today shallow depressions in the ground are all that remain.

The cemeteries remained in existence only a short time. Concluding that it would be easier to manage one large cemetery rather than several small ones, the War Department transferred the Wilderness dead to Fredericksburg National Cemetery in the late 1860s.

Having collected all that a thorough search could discover, graves were dug….Ten skulls were placed in each coffin, which was then filled with bones – the lid screwed on, and…lowered into their last resting place, unknown, but not unhonored nor unsung.

Lieutenant William D.F. Landon

1st United States Volunteer Veterans.

Caption to the right of the photograph:

Artist George Leo Frankenstein made this watercolor of the cemetery (left) during a visit to the Wilderness in the late 1860s. A photographer snapped a picture of the cemetery interior (right) at approximately the same time.

Map and directions to Tour Stop 7

Tour Stop 7 is on the south side of Orange Plank Road 0.4 mile east of the intersection with Hill-Ewell Drive and 0.4 mile west of the Brock Road intersection. (38°17’52.8″N 77°42’52.0″W)

Directions to the next stop on the Auto Tour:

Directions to the next stop on the Auto Tour:

Continue northeast on Orange Plank Road. Stop Eight is about 0.3 mile ahead on the the south side.