The Crater • Tour the Battlefield • Battle Maps • The Armies • Petersburg Timeline

The Battle of the Crater grew out of an unusual situation. One of Burnside’s Ninth Corps regiments, the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry, made the furthest advance in the failed Union attacks on June 18, reaching a point barely 500 yards from the Confederate defenses before they dug in. They were huddled below the crest of a ridge, but part of their lines were sheltered from view by the topography. The regiment was made up of anthracite coal miners and commanded by a mining engineer, Colonel Henry Pleasants.

Pleasants had heard his men comment that, “We could blow that damned fort out of existence if we could run a mine shaft under it!” He did a risky survey along his trench line, measuring distances and calculating angles while dodging sniper fire. Concluding that the thing was possible, he took his plan up the chain of command. Burnside was enthusiastic and told Pleasants to begin digging while he sold the plan to army headquarters.

Meade, an engineer himself, had serious doubts. The tunnel was longer than anything ever attempted and the location not very good, hitting Confederate lines where they had considerable depth and strong flanking positions. But he gave the go-ahead, more to keep the men occupied in the stagnating trench warfare than in any hope of results.

This didn’t mean that Pleasants and his men would get any help. The Army of the Potomac’s Chief Engineer, Major James Duane, scorned the project as “clap-trap and nonsense” and refused to provide any material support. Necessities such as tools, sandbags, wheelbarrows and timber to shore up the shaft were unavaiable and had to be improvised from scrounged materials.

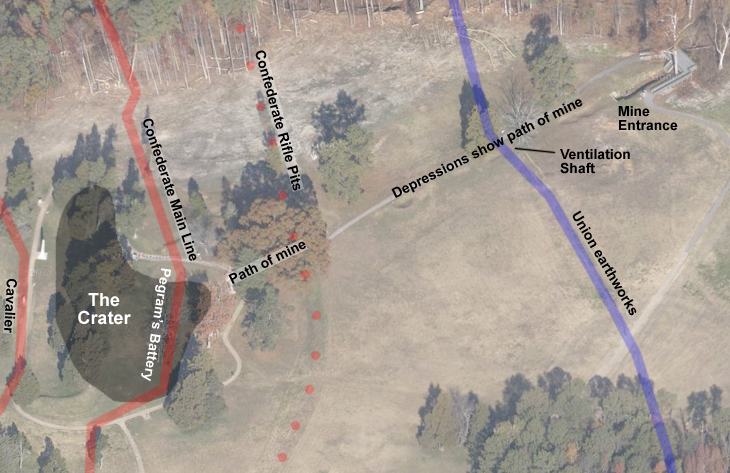

Digging began on June 25 and the men were soon excavating forty feet a day. One of the first problems was providing air for the miners. Pleasants dug a ventilation shaft about 120 feet down the tunnel, but still out of sight of the Confederate lines. An airtight cloth seal was placed between the shaft and the entrance and a wooden duct was built from the mine entrance to the work area. A small fire was kept burning beneath the ventilation shaft. The fire drew stale air from the tunnel up the ventilation shaft, which was replaced at the digging area by fresh air that was drawn in the wooden duct.

The entrance to the mine shaft. Confederate lines were out of sight on the other side of the slight rise that hid the tunnel entrance.

The second problem was a stratum of marl that slowed digging to a crawl. The tunnel was already heading uphill, both to follow the contour of the terrain and to provide drainage. Pleasants increased the angle of climb until it climbed out of the marl into an easier layer.

The shaft was completed on July 17 with a total length of 510 feet. Two galleries branched out in a T to each side to hold the gunpowder, one 37 and the other 38 feet long. Over 18,000 cubic feet of earth had been moved, all by hand, in less than a month.

Positions of the mine, the Crater, and the Union and Confederate lines superimposed on an aerial view of the battlefield. The Main Confederate line was on high ground, with rifle pits on lower ground that sloped away from it. A reinforcing earthwork raised above and behind the main earthwork, called a Cavalier, was behind the redoubt that contained the four guns of Pegram’s Battery. The Union earthworks were about 400 yards down the hill. The mine entrance and ventilation shaft at the upper right of the photo were not visible from any of the Confederate positions due to the drop in elevation.

On July 27 Meade gave his approval to prepare to set off the mine. Pleasants requested 12,000 pounds of gunpowder and 1,000 yards of safety fuse. He got neither, receiving 8,000 pounds of powder and lengths of lesser quality blasting fuse that would have to be spliced together. It took six hours to carefully fill the galleries at the end of the mine with powder. Three parallel lines of fuse were then laid along the gallery floor. Finally, the mine was ‘corked’ with 1,000 cubic feet of sandbags. By the end of the afternoon on July 28 everything was ready.

The mine was ordered to be blown at 3:30 a.m. on July 30. At 3:15 Colonel Pleasants entered the mine and lit the fuse. Everyone waited, the tension almost unbearable in the humid summer heat.

Nothing happened.

By 4:15 it was obvious there was a problem. The fuse had probably gone out, but it was possible that the inferior fuse was just burning slowly. Two very brave men, Lieutenant Jacob Douty and Sergeant Henry Rees, volunteered to crawl up the dark tunnel into the heart of the giant bomb and see what went wrong. They found the fuse had gone out at one of the splices only 100 feet from the entrance. The two men fixed the break, re-lit the fuse, and moved out as fast as they could.

At 4:40 a.m. there was a muffled thunder and a strong concussion. Then Elliott’s Salient and the ridge it stood on disappeared in a fiery blast.

The crest of the ridge was now a smoking crater 170 feet wide, 50 feet across and 30 feet deep. Four cannon disappeared along with 22 artillerymen of Pegram’s Battery and 256 infantrymen of the 18th and 22nd South Carolina Infantry. Many others were badly injured, partially buried, paralyzed with shock or hysterically running for Petersburg.

Colonel Pleasants and the 48th Pennsylvania had earned a break. They would not take part in the actual assault – a very lucky thing for them.