The Crater • Tour the Battlefield • Battle Maps • The Armies • Petersburg Timeline

At 2 p.m. the Confederate guns intensified their fire. The attackers swept down toward the crater, sheltered at first by the terrain. As they moved into view of the crater its defenders ripped them with rifle fire. In the last minutes before they reached the crater they were exposed to Union artillery and great gaps were torn in the ranks. But the wave of attackers pushed on and rolled over the Union defenders at the crater’s edge, cutting into the dense, disorganized mass of men with bayonet and knife.

Some of the defenders fought and died. Some tried to surrender – and many of them died as well. Very few of Ferrero’s African-Americans were given an option. A huge mass of men broke out of the rear of the crater and rushed across the artillery-swept no-mans-land to Union lines, losing more men in their retreat then they had in the original attack. As the fighting died out in the crater the survivors of Hartranft’s three Michigan regiments slipped out of their captured Confederate works south of the crater and returned to their lines.

The last of the killing was over before 2:30. In less than ten hours Burnside’s Ninth Corps had lost 3,500 men – more than a quarter of its strength.

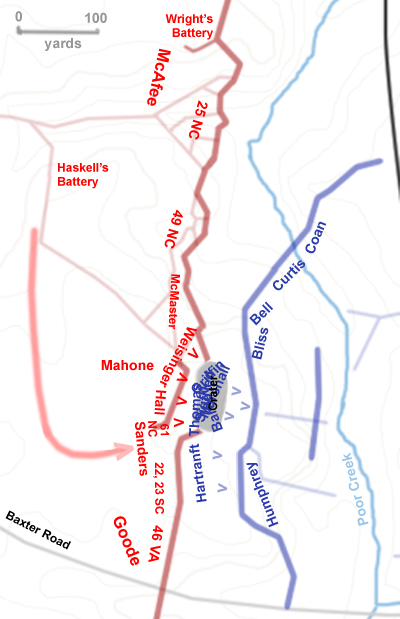

Confederate losses were about 1,500. Over 700 of those came from Elliott’s Brigade, more than a third of them in the instant of the explosion. Mahone’s counterattack cost his division another 600.

The wounded and the Confederate dead were taken out of the crater and the Union dead tossed in and covered over. Working through the evening and night, the pit was incorporated into the Confederate defenses by the next morning.

James Ledlie was censured for his conduct, having spent the battle in his bunker, drinking. He left the army and formally resigned in January.

Ambrose Burnside testified for three days to a Court of Inquiry before departing on leave. The Court found Burnside primarily responsible for the failure of the attack. He never returned to the army.

Ulysses S. Grant summed up the Union effort in a telegram to General Halleck in Washington. “The saddest affair I have witnessed in this war.”

William Mahone was hailed as the hero of the hour. He was promoted to major general and confirmed in permanent command of his division. After his death the Petersburg Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy erected a monument to him which stands just to the west of the Crater today.